Game Of My Life #07: The most emotional championship

This article was written by Alex Feuerherdt.

The situation before the game

When the clock approached the 90 minute mark on the penultimate matchday of the 2000/01 season, there was every indication that FC Schalke 04 and FC Bayern would go into the final matchday level on points at the top with Schalke being ahead on goal difference by five goals only. If both matches had ended right now, the situation would arguably have greatly favored Schalke whose last match of the season was a home game against 16th placed Unterhaching, while Bayern had to make the trip to Hamburg to face HSV.

But in is this 90th minute, both teams’ outlook completely changed quite spectacularly: Schalke, who were away to Stuttgart, conceded a last minute goal through Krassimir Balakov, sealing a 1-0 defeat for Schalke, while only seven seconds later Bayern managed to turn around their home match against Kaiserslautern with a goal from Alexander Zickler, whose 2-1 clinched the victory for Bayern. So as it stood, Bayern would kick off on last matchday three points ahead of the “Miners”, which meant that winning one point away to Hamburg would be enough for them to secure their 17th Bundesliga championship and third title hat-trick in the club’s history.

But nothing this season was as consistent as Bayern’s inconsistency. They had already suffered nine (!) defeats, some equally as unexpected as unnecessary ones like that at home against Rostock or away to Unterhaching (0-1 each) among them. As if to make up for their poor Bundesliga form, their performance on the European stage was spotless: Two years after their traumatic last minute defeat against Manchester United in the Champions League final in Barcelona, they reached the final again to face CF Valencia in Milan only four days after the match in Hamburg.

In case you missed it

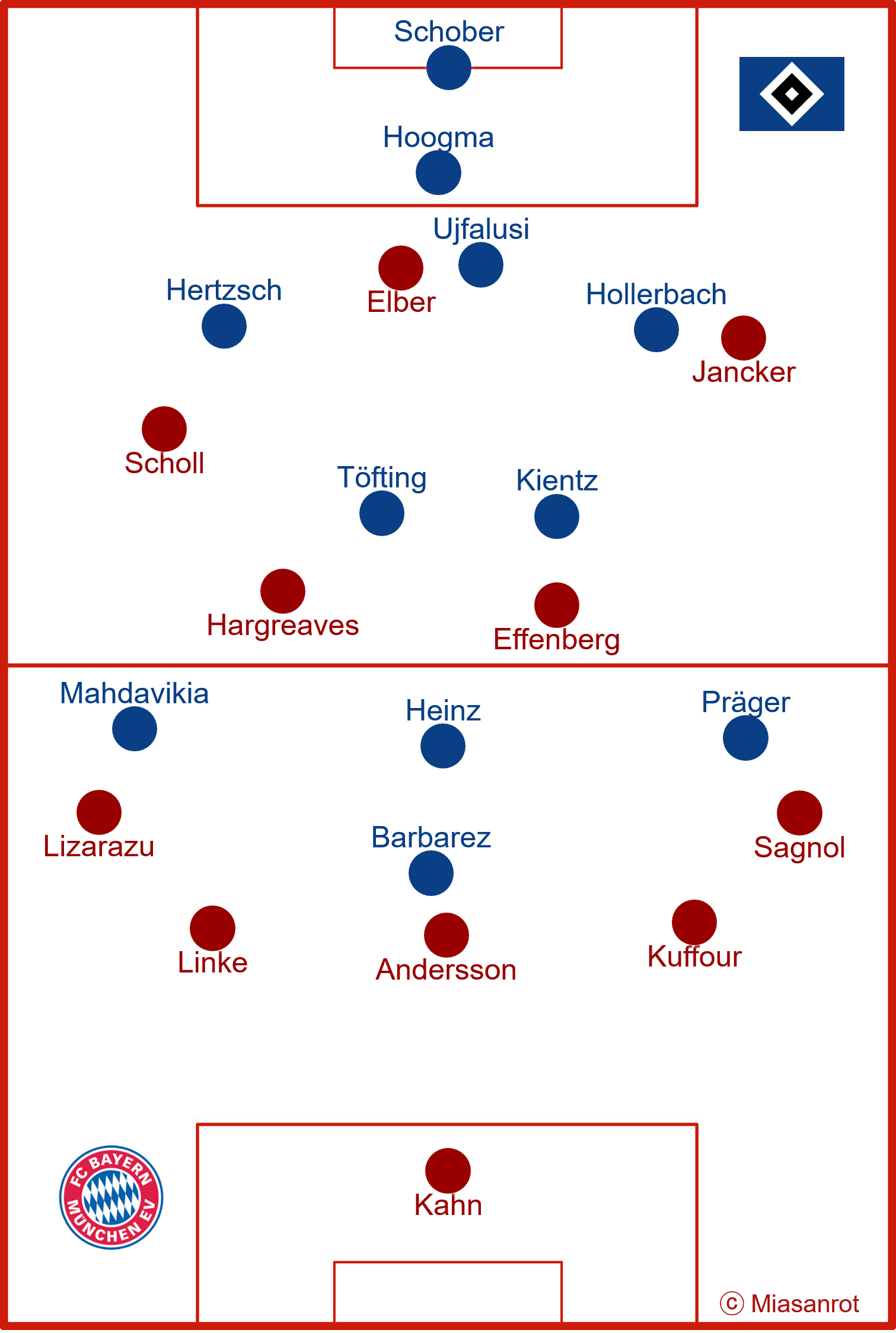

The starting lineups

HSV coach Frank Pagelsdorf had to do without midfielder Niko Kovač and defender Milan Fukal, who were replaced with Jochen Kientz and Ingo Hertzsch. Bayern coach Ottmar Hitzfeld made three changes to his side from the match against Kaiserslautern: Roque Santa Cruz, Ciriaco Sforza and suspended Hasan Salihamidžić dropped to the bench, Giovane Elber, Mehmet Scholl and Willy Sagnol came in.

In front of second goalkeeper Matthias Schober for only his third Bundesliga match of the season, Hamburg started with a back four with Nico Jan Hoogma positioned in a sweeping role centrally behind Ingo Hertzsch and Bernd Hollerbach as full-backs and Tomáš Ujfaluši in central defense. Hertzsch had to deal with Mehmet Scholl, who liked to drop back to midfield, while Hollerbach took on Carsten Jancker. Ujfaluši managed to keep center-forward Giovane Elber almost completely in check throughout the game.

Hamburg tried to oppose Owen Hargreaves and Stefan Effenberg in Bayern’s engine room with the physical presence and power of Jochen Kientz and Stig Töfting. In attack, they started with a three men front line consisting of Sergej Barbarez in the center, Mehdi Mahdavikia on the right wing and Roy Präger on the left wing. Slightly behind the three, Marek Heinz played in the central playmaker position. Bayern’s defense, as per usual, was made up of Thomas Linke, Patrik Andersson and Sammy Kuffour in a back three in front of Oliver Kahn in goal, with offensive-minded Willy Sagnol as right and Bixente Lizarazu as left wing-backs.

The first half

The beginning of the match had to be slightly delayed, because a slew of bananas were thrown in the direction of Oliver Kahn from the stands behind his goal – an equally as common as unsettling occurrence at Bayern games away from home back then – which had to be removed from the pitch first. A few minutes after kick-off, the game had to be interrupted for a few minutes, because billows of pyrotechnics-induced smoke wafted through the stadium. After that, the home team, occupying a mid-table position and devoid of any hopes or worries, took the initiative galvanized by a frenetic crowd that was craving a sensation. Bayern sat back, allowed Hamburg to control the game and attempted to slow the game down when in possession.

However, there was no real need for Bayern to take a risk, because to many people’s surprise, Unterhaching had gone two goals up in the Parkstadion in Gelsenkirchen. Meanwhile, Hamburg had two good chances through Barbarez, both of which Kahn managed to stop with his customary strong reflexes. On the other end, Jancker was denied by Schober two times. While this match went to half-time goalless, Schalke managed to level the score by striking twice in quick succession before half-time, making it 2-2.

The second half

In the second half, the match picked up where it left off before half-time: Hamburg invested more in the game while Bayern mostly tried to keep the ball and occasionally hit HSV on the break. One of these attacks saw Jancker putting a cross from Lizarazu in the back of the net, but the goal was disallowed for offside – a wrong decision. In the meantime, Unterhaching went ahead again 2-3, but the hosts eventually turned the game around to win 5-3. Now the case for Bayern was as straightforward as they come: they could not afford to lose if they wanted to win the championship.

This seemed to be an additional stimulus for Hamburg and Bayern did indeed threaten to lose the championship at the last moment: First Hargreaves and Kuffour failed to clear their lines twice after two crosses (but got away with it), but on the third attempt, Barbarez won an aerial duel against Patrik Andersson and from the inside of the post the ball bounced over the line. Had the final whistle gone in both games at this moment, Schalke would have been Bundesliga champions. Bayern now desperately tried to avert the impending catastrophe, but their attacks were too haphazard and disorganized.

(Image: Andreas Rentz/Bongarts/Getty Images)

Until deep in stoppage time Stefan Effenberg played a pass with the outside of his right foot towards substitute Paulo Sergio, who had come on for Mehmet Scholl, which Ujfaluši just managed to poke back to his goalkeeper. Instead of simply kicking it out as far as possible, Schober picked the ball up with his hands – a clear violation of the back pass rule. Referee Markus Merk inevitably gave an indirect free kick ten meters out from Hamburg’s goal. And just the same as they did the week before, Bayern struck back literally at the last second: Effenberg teed the ball up for Patrik Andersson, whose strike found the sole hole in the wall and landed in the back of the net for the equalizer, making it 1-1. Unbelievable.

Things that caught our eye

Onward, ever onward

“I took the ball out the net and didn’t think much about it. But then it struck me: There’s at least another three minutes to play in this game. And I thought, look, we’ve got to carry on! Just carry on! Carry on regardless! Why shouldn’t we be able to turn things around? The stuff that can happen in three minutes. We still believed in ourselves in the 90th minute, we had the desire. You can force your luck if you only try. That’s the character, that’s the spirit that made us champions.” These are the famous words that Oliver Kahn said in his post-match interview to the “Kicker”.

(Image: Andreas Rentz/Bongarts/Getty Images)

As a matter of fact, Bayern’s championship was not based on an elegant playing style or high individual class of their players, but on tireless determination and endless stamina. The two goals by Zickler and Andersson, which were Bayern’s deciding last two goals at the end of the season, epitomized this in a nutshell. The Bayern players knew from their own bitter experience of the Champions League final two years earlier what it feels like to lose a title at the last moment. But instead of breaking them, they learned a valuable lesson from this: Everything is possible until the final whistle blows. It’s never over till it’s over.

This spirit was probably embodied best by Kahn, who shoved his way through half the HSV team to intimidate the opposition before the free-kick, and Stefan Effenberg: “I looked at the stadium clock and the time was precisely 5.16 p.m.”, he said to the “Kicker”. “I knew we would get another one or two chances. And then the ref called the back pass.” It was the 32 year old who decided that Patrik Andersson would take the free kick. “From this distance it is always best to go for power, which really made Patrik the only choice. I said to him: Just leather it into the back of the net and let’s go home. And so he did.”

The most important goal of his career

When Bayern lost the Champions League final 0-3 against Olympique Lyon and club president Franz Beckenbauer criticized the performance at the banquet after the match as “old age pensioners football” as you would see at a “Uwe Seeler Legends” match, this criticism included Patrik Andersson. The center-back did not have a good match, the season had been far from ideal for him anyway due to several injury problems. But Andersson, having joined Bayern for 4 Mio. DM from Gladbach before the 1999/2000 season, improved greatly after the disastrous match just like the rest of the team. He became Bayern’s boss in defense, a pillar of consistency.

(Image: Andreas Rentz/Bongarts/Getty Images)

However, he was not particularly known for his goal threat at Bayern, which made him an all the more remarkable selection to take the all-important free-kick. “When I stepped up to the ball I thought: Keep cool, now it’s up to you”, Andersson later said. “All I wanted is to give the ball a clean hit. I didn’t see a hole in the wall, I just wanted to force the ball through. With power. And then it went in. My head exploded, it was a total outburst of emotions.” The goal was his first and only for FC Bayern – and the most important one of his career.

Four days later, Patrik Andersson almost became the tragic hero in the Champions League final. After barely two minutes, he conceded a penalty with a handball, which Valencia converted for the lead. Later, he failed to score in the penalty shootout against Santiago Cañizares. But ultimately he and his team carried the day as they had done in Hamburg. Having won the double, the then 29 year old left Bayern after only two years at the end of the season. He joined FC Barcelona for a fee of 15 million DM.

Football is amazing – and cruel

The clock showed 5.18 p.m. and 12 seconds when the final whistle blew in the Parkstadion in Gelsenkirchen – the final whistle at all for a Bundesliga match in this stadium. FC Schalke 04 had won their game against Unterhaching 5-3. At the same moment, Bayern was a goal down. 44 seconds later, the (false) news made the rounds that the match in Hamburg was over. All hell broke loose at Schalke. Floods of spectators swarmed onto the pitch, celebrating their team’s first championship for 43 years with wild abandon. They were indescribable scenes of rapture. How could one have begrudged these people their success after all these years?

But suddenly the images from Hamburg flickered across the video wall in the stadium: the match there was not yet over. Anyone who cared to watch could see how the former Schalke player Matthias Schober picked up the ball with his hands after Ujfaluši’s back pass. How Markus Merk blew the whistle. How Stefan Effenberg placed the ball. How Patrik Andersson scored. How the Bayern players cheered. Schalke were champions for just four minutes, then the euphoria gave way first to paralysing horror and finally to unrestrained, abysmal despair. It must have been a wicked soul who did not feel with Schalke and their fans – had Bayern not made the same experience just two years earlier in the drama of Barcelona? Football can be amazing. And incredibly cruel.

What the game meant

It is pure conjecture, but not a totally unreasonable one: If FC Bayern had lost the championship in Hamburg, they would probably have lost the Champions League final as well. At the very least, it would have been a stupendous achievement by Ottmar Hitzfeld to restore the team to a level that would have given them a fighting chance in the final within days of another Barcelona-like last-minute title loss. But the way it turned out, the team traveled to Milan on a wave of elation and full of confidence to overcome the odds there once again: falling behind through a penalty early, missing a penalty kick themselves, then converting another, and finally winning the penalty shootout, courtesy of a world-class Oliver Kahn.

For many Bayern fans who consciously followed the last matchday of the 2000/01 season, this championship is still the most emotional one of all. The drama of the last two matchdays can hardly be overstated and it is still difficult to grasp today. In fact, the turn of the millennium was a crazy time for the record champions’ fans: one year after the painful defeat against ManUnited, FC Bayern managed to defend their title on the last matchday, because Bayer Leverkusen spectacularly lost to Unterhaching in the parallel match; and with the DFB-Pokal win against Werder Bremen, they took revenge for the defeat one year earlier. And then one year later the double of championship and Champions League title, both secured at the very last second.

It could not have come as a surprise that after such an intense period of narrow wins and excessive emotional ups and downs, something had to give. The players must have felt or known that the years between 1999 and 2001 were a euphoria-saturated rollercoaster ride that could not last forever. At least they must have felt that they would not be able to repeat their international successes at the same level. The victory over Valencia made up for the gruesome night in Barcelona and the championship hat-trick after a mixed season in the Bundesliga made it clear that they would put the competition in their places – on the last matchday if need be. The icing on the cake finally came at the end of November when Sammy Kuffour scored in extra time to win the Club World Cup against Boca Juniors of Buenos Aires. Bayern just liked to keep things exciting at the time.