Game of my Life #06: The grandmother of all defeats

In the case of FC Bayern, this phenomenon is especially apparent: The Bayern team of the 70s is almost mythically revered because of its three European Cup triumphs from 1974 to ’76, the Champions League winners of 2001 around Kahn and Effenberg are venerated like heroes, and the treble winning team of 2013 has become the stuff of legend already. Everything before and in between has been fading from memory and will sooner or later be totally forgotten. And yet we all know that it is often only a matter of small margins and minute details that makes the difference between winning or losing, between triumph and despair. How would we look at the history of Bayern today if Schwarzenbeck’s belter in the dying moments of the 1974 European Cup final had not brought about the replay match? What if just one of Zahovic, Carboni, or Pellegrino had scored in the penalty shootout in 2001? What if Dieter Hoeneß’s goal in 1982 had… – well, what exactly was it with that goal again?

The situation before the match

The way back to the top

May 26, 1982 saw FC Bayern compete in a European Cup final for the first time since 1976. Bayern supporters today know only too well how long a time six years can feel. Yet the crucial difference between the situation back then and now is that the final in 1982 was supposed to cap off a period of steady progress of the team beginning in 1978 with the return of Breitner and the appointment of Pal Csernai as head coach with a European title as the crowning achievement.

With Bayern dropping to a relegation place in the table in the 1977/78 season for a time, it was by no means certain that their period of sustained success in the 70s would not remain a one-time exception, an ephemeral apogee never to be reached again. Most of the players of the golden generation had either already left the club or were approaching the end of their careers while the club could not afford to sign new stars, and new up-and-coming talents from their own ranks like Beckenbauer, Müller, and Maier before was nowhere in sight. All in all, the once so mighty FC Bayern was well on its way to becoming just another ordinary Bundesliga club.

But only two years later, the situation had turned around completely: Due to a unique blend of zonal and man marking, dubbed the “Pal-System”, which was perfectly matched to the qualities of returnee Breitner, as well as the transformation of a talented but not overly dangerous striker into a one-man attacking army, Bayern had managed to return to the top of not just the Bundesliga but also Europe.

Karl-Heinz Rummenigge had already won the European footballer of the year award in 1980, when 24 of 25 judges named him their number one choice. But especially the vote of 1981, when „Breitnigge“ came first and second in the ranking, shows how much of their former reputation the club had regained in the beginning of the 1980s. Once again, Bayern was considered the best team in Europe.

The way to the final

Whereas in 1980/81 Bayern had been eliminated from their first European Cup participation since 1976/77 with an unfortunate defeat on away goals against Liverpool in the semi-finals (which would be the beginning of a five year consecutive period of being knocked out by British teams), in 1981/82 their route to the final all of a sudden seemed to be clear after CSKA Sofia had sensationally beaten Liverpool in the quarter-finals.

But this was easier said than done:

For one, Bayern had to get past CSKA Sofia first, a team that was playing a technical football of the highest quality under their coach Nikodimov. Not much of a surprise therefore that in the first leg Bayern was three goals down without reply after no more than 18 minutes. Only the substitution of Dieter Hoeneß, whose raw power the Bulgarians could not really contain, changed things for the better. Bayern “only” lost 4-3 in Sofia and with a 4-0 victory at home, they eventually cruised to the final.

Moreover, in the 1981/82 season, the „Breitnigge“ era almost appeared to have its heydays behind it. Although Hoeneß, Rummenigge, and Breitner were the European Cup’s three top scorers, although Bayern was able to win the DFB-Pokal in a dramatic final thanks to “Turban-Dieter”, they only finished the Bundesliga season in third place having conceded an incredible 56 goals. While they had a perfect start to the season with a 10:0 points record after five games, they lost far too many away games during the rest of the season (10 away defeats in total) to be able to lay any serious claim to the title. The defense in particular was the weak link. Quickly executed counterattacks and an aggressive pressing turned out to be an effective antidote to Bayern’s rather sluggish possession-based game. Aston Villa, Bayern’s opponent in the final, should have a field day with this.

The opponent: Aston Villa

If Bayern was beyond their peak in 1981/82, this was all the more true for Aston Villa. Having yet been English champions the season before, they only managed to finish eleventh in the 1981/82 season. A change in the position of head coach in February did not have a palpable effect. But they looked an entirely different proposition in their European Cup matches. The heart of their team was a very resolute and robust defense. Dynamo Berlin was the only team that was able to score against them in their European campaign. Reykjavik, Dynamo Kiev, and Anderlecht all failed to do so. In attack, the team struck their opposition with their typically British vertical attacking football and equally fast and technically skilled wingers. These would normally cross the ball to center-forward Peter Withe, but in European Cup matches he often rather played the role of the towering main target man in attack to knock down and distribute second balls to his advancing teammates.

(Image: Allsport/Getty Images)

Aston Villa’s place in the final was by no means a fluke, even though their road there was a bumby one. They progressed against Dynamo Berlin on away goals, in their two-legged tie against Dynamo Kiev they were helped by the fact that for weather reasons the first leg had to be moved from Kiev to Simferopol, where the extremely rough pitch did not favor Lobanowski’s modern combinational playing style. Aston Villa’s home turf in Birmingham was in an even more horrendous condition. The morass-like surface completely extinguished any hopes of a controlled build-up play, which again favored Aston Villa. They availed themselves of a lot of long balls over the top and high crosses to circumvent the unplayable center of the pitch, scoring two goals. To top things off, their place in the final after beating Anderlecht in the semi-finals had to be affirmed by a court ruling after there had been violent riots by some of the spectators during the return leg, which saw an English supporter invade the pitch and cause the match to be briefly interrupted. Anderlecht’s official protest, however, was turned down. The only consequence for Aston Villa was that they had to play their next European Cup home game in front of an empty stadium. And so the final in Rotterdam on 26 May, 1982 was ready to go.

The mood before the match

Bayern were made out to be the clear favorites. If anything could give Villa hope, it was that since 1977 the competition had exclusively been won by English teams: 1977 & 1978 FC Liverpool, 1979 & 1980 Nottingham Forest, and 1981 FC Liverpool again. Nottingham Forest in particular were not considered favorites before either of their two title wins in a row, which gave Villa, who stylized a self-image of “tough to beat” at the time, additional confidence. Paul Breitner had called English football “naive” just the year before, which the English press left no opportunity unused to confront and stir up Aston Villa’s players with.

In case you missed it

The first half

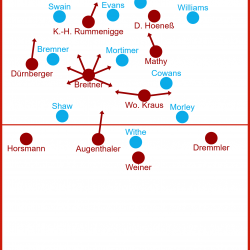

A little bit of that needle could still be sensed in the first half of the match. FC Bayern, as always, were intent on controlling the game from dominance in possession, which they did with reasonable success in the opening minutes. It was obvious that they wanted to keep Villa out of the game as much as possible. Villa answered with challenging Bayern’s players aggressively and advancing the ball forward quickly whenever they had won it. Then in attack, it fell to Morley and Shaw to create opportunities by taking on and getting past Bayern’s robust defenders Dremmler and Horsmann. Although Gary Shaw arguably played the best season of his life and would later receive the award of Europe’s best young player of the year 1982, it was Tony Morley who with his fluid agility made Bayern’s somewhat ponderous and rough defense look completely overtaxed at times. The giant Peter Withe mainly had to deal with Klaus Augenthaler in the center. Although Augenthaler had prepared for this duel in training the day before against a similarly framed Dieter Hoeneß, Withe repeatedly managed to cause problems for him and the other center-back Hans Weiner, who often helped Augenthaler out against Withe. Since the vulnerable Bayern defensive line, with its largely zonal marking approach to defending, was mainly concerned with protection, acted cautiously and sat very deep, large unoccupied spaces in midfield – or “acres of space”, as the original English commentary aptly put it – emerged. Withe often fell back between Bayern’s defense and midfield lines to make himself available for long balls. As Augenthaler was careful not to be drawn out of position, it was not uncommon for the 1.88 m tall Withe to be confronted by the 15 cm shorter Wolfgang Kraus. As a consequence, Withe could bring a lot of high balls under control in the center and distribute them to the outside without facing too much pressure.

Due to their two deep defensive lines, Bayern’s way to the opposite goal was always quite long, constantly requiring them to bridge a large area when transitioning from defense to offense. This was not a disadvantage per se as Paul Breitner was ideally suited to play in this way. Breitner was a unique hybrid of a playmaker and box-to-box midfielder, whose specialty it was to advance with long strides, the ball at his feet, from defense to attack. However, at the time of the match, he was not really fit: He had not played a single Bundesliga match over the full distance since Bayern’s comprehensive defeat against Hamburg on matchday 28. Just 11 days prior to the final, Breitner had to be replaced during the game in Gladbach due to a strain he had suffered shortly before on international duty in a meaningless friendly between Germany and Norway. He was simply physically unable to keep up his exhausting style of play for all of 90 minutes.

This was one of the reasons why Bayern, the same as Aston Villa, consistently tried to pass over midfield with long balls. High balls from Augenthaler to Dieter Hoeneß were a recipe that had worked well in the semi-finals against CSKA Sofia and in the DFB-Pokal final against Nuremberg. The problem for Bayern in this game, however, was that Aston Villa was used to dealing with physical center-forwards like Dieter Hoeneß week after week in their own league. Dieter Hoeneß could spread neither fear nor fright among the physically strong defenders and caused hardly any goal threat in the first half. Another weak point in Bayern’s eleven was youngster Reinhold Mathy, who had only been called up to the first team very recently. He, too, was struggling to provide a link between defense and offense all game. Nominally positioned in right midfield, he again and again drifted towards the central playmaker position, adding just another body to the already crowded centre and leaving his right side practically vacated. Whenever Dürnberger launched into one of his occasional attacks down the left wing, there was a single large hole on the right-hand side, as right-back Dremmler hardly ever participated in attacks. Only Paul Breitner, who already had an enormous workload to shoulder as it was, tried to fill the void on the right from time to time. Whenever he was on the ball, danger for Villa was in the air. This was particularly the case towards the end of the first half, when Aston Villa were increasingly unable to fill the occuring gaps despite their best efforts to do so. Part of the reason was also Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, who had been invisible for a long time, but would now more and more often fall back to get the ball.

Rummenigge, what a man…

Rummenigge was a larger-than-life figure at the time: As a two-time European footballer of the year, he not only became top scorer for two years in a row at a time when the Bundesliga was undoubtedly the strongest league in the world, he also was European Champion, Germany’s Footballer of the Year 1980, top scorer of the European Cup 1981, ranked “world class” by German football magazine “kicker” two years in a row, scorer of the Goal of the Year 1980 & 1981, captain of the national team – and the list goes on. In short, it would be no exaggeration to compare his reputation at the time to the present-day reputation of a Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo. Interestingly, his reputation was not even based on what he was actually capable of doing on the pitch; more important was what he was considered capable of doing. In every schoolyard there were rumors of heroic deeds and breathtaking technical feats he was supposed to have accomplished. In times without Pay TV, DVRs, and the Internet, when not every game was available everywhere all the time, most of the available footage of him consisted of the spectacular clips of his goals of the month or year, which shaped his public image accordingly. As a result, many people went into a football game in which Karl-Heinz Rummenigge took part with the expectation that something spectacular would happen with him being at the center of it. So too for this match. Bayern supporters hoped for a miraculous feat out of nothing by the exceptional player, especially in such a disjointed affair as the first half. Aston Villa supporters, on the other hand, took a deep breath every time Rummenigge had a touch on the ball. If you watch the game with the original English commentary, you can feel the disappointment of co-commentator Brian Clough in the middle of the first half, as he realized that Rummenigge seemed to be an earthly phenomenon after all. But just as the spectators were beginning to wonder whether the fabled legends about Rummenigge had been blown completely out of proportion during pre-match build-up, he hit two spectacular strikes towards Villa’s goal in quick succession around the 30th minute of the match: First, substitute goalkeeper Nigel Spink (in his second competitive game overall and first in three years) parried his marvellous shot with a brilliant reflex, after Breitner had won the ball previously. A few seconds later, Rummenigge got on the end of a cross from Breitner and almost scored with a spectacular overhead kick from the edge of the penalty area, restoring his awe-inspiring aura in one fell swoop.

When the referee blew the half-time whistle after yet another Rummenigge chance, the game’s momentum had clearly shifted to Bayern. While it was initially difficult to stop the energy and commitment of Villa and their raid-like attacks, the last 15 minutes of the first half saw Bayern successively win control of the match. Breitner was increasingly able to impose himself on the game and involve his congenial partner in crime, Rummenigge. Bayern’s players attacked the opposition players higher up and thus managed to win the ball in the opposing half already. The defenders also joined in the offensive at times. It seemed only a matter of time before Bayern would be able to capitalize on their superiority.

The second half

Both teams returned to the field without any changes in personnel. In the opening minutes, the momentum of the game remained with Bayern with the run of play largely resembling the final minutes of the first half, when Bayern were in firm control and pushing for the lead. A few tactical adaptations to Bayern’s side made for an even clearer dominance at the beginning of the second half:

For one thing, Bayern were visibly determined to win more of their challenges now. Especially Wolfgang Dremmler made some wild tackles that would be definitely sanctioned today. But thanks to this increased aggressiveness, Bayern was able to successfully cut short Aston Villa’s phases in possession to a minimum.

On the other hand, Weiner now got more involved in covering and aerial duels so that Augenthaler could interpret his defensive role a little bit more loosely. As a result, he had more opportunities to get involved in Bayern’s offensive game with dynamic runs or with long balls up front to initiate attacks. In contrast to the first half, the main target was no longer Dieter Hoeneß. Instead, Augenthaler deliberately hit long balls into the free space behind Villa’s defense frequently. This sped up Bayern’s formerly rather cumbersome attacking game and brought more verticality into their game.

In addition, Günter Güttler replaced Reinhold Mathy in the 52nd minute of play, which nominally seemed to be a defensive change. But the fact that Güttler more faithfully kept his position in right midfield than Mathy helped the structure of Bayern’s game at first. On the one hand, this gave Breitner a bit more space in the center, on the other hand it allowed Dremmler to participate in attack down the right wing without leaving the right side completely exposed.

(Image: Bongarts/Getty Images)

An irresistible Augenthaler dribble over half the pitch, in which he unfortunately overlooked three completely open teammates in the penalty area in favor of a shot from distance that went wide, initiated the best Bayern phase of the game in the 57th minute. After a one-two with Breitner, Bernd Dürnberger missed with a free shot in the 60th minute, which set off a flurry of chances in the following minutes: A flying header by Augenthaler (63rd minute) was followed by a chance for Hoeneß, who was not quite able to put a cross from Dremmler over the line (64th minute). Only one minute later, Hoeneß again missed the goal by only a few centimetres after a cross from Horsmann.

But just as the team from England was completely on the ropes and a Bayern victory seemed only a question of by how many goals, Aston Villa came up with their only real chance of the second half in the 67th minute. Dremmler slipped as he too eagerly tried to go after Shaw on the right side, Shaw played the ball to Morley, whose quick feet left Weiner for dead. Augenthaler in emergency mode decided to shift his attention to Morley, losing sight of Withe in the penalty area, who suddenly appeared completely free in front of Müller, received the ball from Morley, and knocked it in from close range.

The game was utterly turned on its head. Bayern did their utmost to level the score again, but failed to find a way against a Villa side that was now sitting deep and waiting for counter attacks. Whenever Bayern managed to push into the penalty area, they lacked the necessary creativity and precision to cause Villa any real problems. Other than a few harmless shots from distance and some half-hearted crosses, they did not come close to creating a threat on Villa’s goal for the remainder of the game. Although Bayern did not surrender, the goal against them seemed to have sucked all life out of a team that had had to fight their way back into a game all too often over the course of the season before (just take for example the DFB-Pokal final against Nuremberg). Even Rummenigge largely disappeared and did not have any more impact on the game, apart from a situation in the 79th minute when he had a free run on Villa’s goal but squandered his chance with an overly hasty finish.

Two minutes from time, the ball did indeed cross Villa’s goal line as Güttler put a long ball from Niedermayer into the path of the onrushing Dieter Hoeneß, but the goal was disallowed for offside. A contentious decision, which in it the absence of proper camera angles and calibrated lines will probably never be finally resolved. And so it was what it was. Bayern were beaten and Aston Villa’s players were laying in each other’s arms.

Three things that remain

1. The end of a era

The defeat against Aston Villa was FC Bayern’s first ever defeat in a final. Until then, the club had won all the 4 European Cup and 6 DFB-Pokal finals in which it had participated. What might superficially appear like nothing more than a mere statistical observation, might have a deeper psychological significance. The almost certain expectation to win every final you contest might lend the extra little bit of confidence and surety that make the crucial difference at this level. Take for example Real Madrid who have won all seven of the Champions League finals they have played.

For Bayern, the defeat in 1982 ushered in a dark period of lost finals which would continue in 1987 and even reach dramatic proportions in 1999. It should take 19 years before Bayern would manage to climb back to the top of Europe in 2001. Even during the darkest moments in the face of the bitter defeat on the evening of 26 May, 1982, nobody would have guessed that it would take this long. Rummenigge was only 26 years old, Breitner was 30. With Pfaff and Nachtweih, the club had already signed two substantial reinforcements to freshen up the squad for next season. That the „Breitnigge“ era was going to end just a year later and that neither of the two would still be playing for the club just two years later, nobody could have predicted.

Because Breitner had already been part of the famous 1974 team (as a defender), his place in FC Bayern’s history books was guaranteed. For Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, on the other head, the defeat in the final meant that his career as a player would remain somewhat unfulfilled. The highest peak of any Bayern player between the eras of Franz Beckenbauer earlier and Oliver Kahn much later should remain uncrowned. And because our memories so vitally depend on prominent dates and exceptional occasions like a title win, it is likely that our appreciation of Rummenigge as a player will fade in time. Will he keep his place in FC Bayern’s all time first eleven after Lewandowski has ended his career?

2. The strength of the squad

Of course, even top teams in the 1980s did not have the same strength in depth in their squads as they have today, where even the substitutes are usually international players of their countries who would be established first team players in other clubs. But Bayern’s squad of 1982 already showed a spread in quality that was more pronounced than for example that of the squad of the 70s. With Breitner and Rummenigge, they had two world-class players, Augenthaler was highly talented, and Dieter Hoeneß thanks to his stature and power could be a difficult player to defend. But the majority of the team was only Bundesliga average, and in goal not even that: Both Müller and Junghans failed time and again during the season, never amounting to a safe pair of hands at the back. In the European Cup final, Pal Csernai could not bring on an additional offensive player to revive his team’s attack after falling behind as both of his main offensive options Hoeneß and Mathy had already featured from the start. The replacement of Mathy with Güttler meant bringing off a junior player for another talent from their own ranks, while the experienced Niedermayr’s greatest asset in bringing about a turnaround was a pair of fresh legs. And since Breitner could not countenance the presence of other skilled players alongside him in midfield and saw the highly talented Sigurvinsson, who would go on to lead VfB Stuttgart to the championship two years later, as a competitor rather than a valuable support, he too was no real alternative.

Bayern had the second highest budget in the Bundesliga after Hamburg, but without Breitner and Rummenigge, the squad did not measure up to international standards. Hence Rummenigge (who had suffered a cruciate ligament stretching in mid-March) and Breitner had to play all the time. In addition, the DFB did not show any consideration for the workload of the stars: At the end of March, the national team went on a mid-season trip to South America to play in Brazil and Argentina. The DFB-Pokal final, which Bayern won only after extra time, also was scheduled for the middle of the season and was played as a mid-week match only three days after the 30th matchday. And even in the most intensive phase of the season, when the games for Bayern came thick and fast, national team coach Jupp Derwall did not want to do without Breitner or Rummenigge. So in between two Bundesliga matchdays, both of them had to play a friendly in Norway, where Breitner promptly injured himself. With having to play a rescheduled match against Werder Bremen in the following week, FC Bayern effectively had to play every three to four days from March up to the European Cup final, with no time to catch their breath. The result was that the team was utterly exhausted and worn out at the end of the season. This was not just evident in the match against Aston Villa. The repercussions of the season still told on the performances of Breitner and Rummenigge at the World Cup in Spain.

3. The “Pal-System”

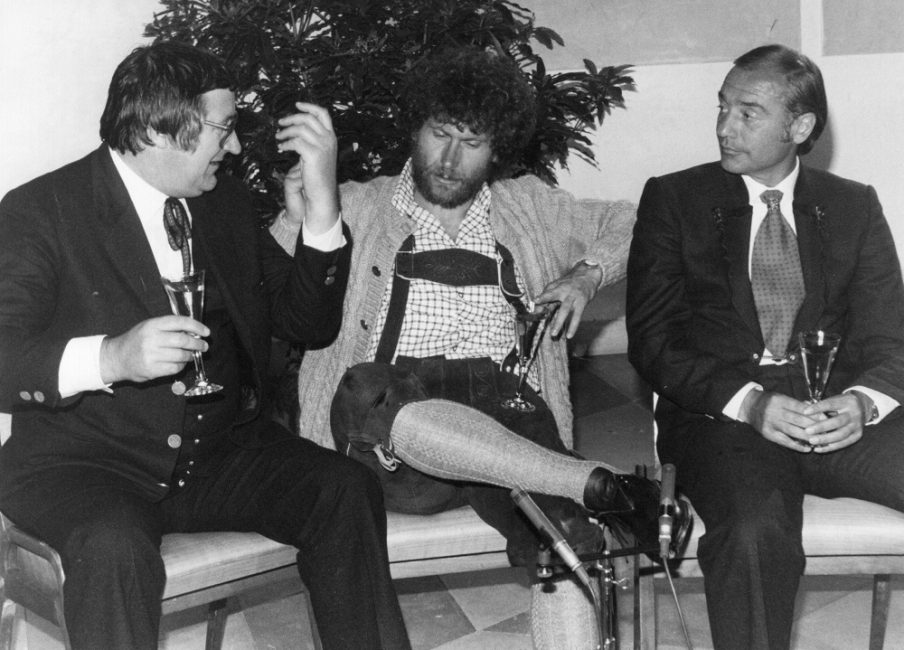

The course of the season in general and the final in particular illustrate that Pal Csernai’s style of football at Bayern was more akin to “heroic football” than “system football”. Sure, the fact that the defenders flexibly switched back and forth between the opponents they marked was certainly a necessary modernisation of the Bayern game. And the fact that Csernai used zonal marking in midfield to allow his players to engage their opponents earlier on also was an important key to the dominance that Bayern came to enjoy in the early 1980s. However, it was not a system that functioned supraindividually, i.e. regardless of the specific personnel. If a key player like Breitner was absent, the same system produced a totally different kind of football. Without Breitner’s presence and tireless work ethic, the team missed direction and the key element that provided balance and linked up defense and offense. Any system, however, that depends on the form and class of some of its specific individual parts, should not be overrated. It was a suitable vehicle to bring out the qualities of its main protagonists, and the zonal marking made it possible for relatively average players in the team to sometimes appear stronger than their individual abilities would suggest, but the term “Breitnigge” ultimately would be a much more apt heading for the period from 1978 to 1983 than “Pal-System”.

(Image: Keystone/Getty Images)

A more lasting effect of Csernai’s time was that he used a real holding midfielder in front of the defense for the first time at Bayern. He thus solved the dilemma that Bayern had been struggling with after Beckenbauer’s departure. Beckenbauer had uniquely been able to compensate for the creative deficits that “Bulle” Roth had as a central midfielder while using his fighting spirit to his best advantage. In the 1977/78 season, Branko Oblak was nowhere near good enough to replace both of them by himself, while Breitner did come closer to meeting this enormously high requirement profile in 1978/79. But it was only the installation of a defensive midfielder next to him that gave the system the necessary stability. A holding midfielder positioned slightly behind a number eight in the centre was to remain a constant in Bayern’s game for decades. From Nachtweih/Lerby to Jeremies/Effenberg, from Wouters/Matthäus to Hargreaves/van Bommel, this distinctive combination shaped the club.