Game Of My Life #03: We are back!

April 16, 1996, Barcelona. FC Barcelona welcomes FC Bayern in the second leg of the UEFA Cup semi-final. Bayern needed a high-scoring draw or an away win to push through to the final in front of a crowd of 115,000 fanatic supporters in the Camp Nou, where Barcelona had not lost a European competition home game since 1992. The game marked the first time the two giants had ever met in a competitive match.

Why the game was special

FC Bayern in the middle of the 1990s – almost an ordinary club.

The 1990s. Football shoes were black. The players on the pitch were numbered 1 to 11. FC Bayern Munich was frequently dubbed “FC Hollywood”, but in sporting terms they were far away from shiny glamour.

The glorious 1970s were but a distant memory, the bloodletting of many top German players to Italy’s greener pastures had left its mark on German football in general and Bayern in particular.

Disappointing years by Bayern standards

Over the last five years, Bayern had won the Bundesliga title only once. The last triumph in the DFB-Pokal had been in 1986, their cup runs were spotted with embarrassing defeats to lower division clubs like Weinheim, Homburg, and Vestenbergsgreuth.

They did not fare much better on the European stage. In 1991/92, they went out of the UEFA Cup after a 2-6 defeat against Copenhagen in the second round. In 1992/93, they were not even qualified, and 1993/94 they again suffered a second round elimination, this time at the hand of Norwich.

In 1994/95, they participated in the still very young Champions League for the first time. They advanced from the group stage and two draws against Gothenburg in the quarter finals were enough to prevail. But in the semis, Louis van Gaal’s Ajax Amsterdam proved a bridge too far, inflicting a comprehensive 5-2 defeat on Bayern. Despite the fairly easy route to the semi-finals, having got there was a respectable achievement.

And then came Barcelona

At the beginning of the 1995/96 season, Otto Rehagel was appointed as the fifth Bayern head coach in four years. After a defeat in the first match, seven consecutive wins under his reign saw Bayern march through to the semi-finals of the UEFA Cup. And now Barcelona waited. Johan Cruyff’s team was one of the top teams in Europe in the early 1990s: from 1991 to 94 they were Spanish champions four times in a row and reached the final of the European Champion Clubs’ Cup in 1992 and 94, which they also won in 1992.

But in the spring of 1996, Cruyff’s era at Barcelona seemed to be beyond its peak. The squad was still top class, but the departures of stars like Laudrup, Stoichkow and Koeman could not be compensated. In La Liga, a fourth place in 1995 and a third place in 1996 were the result. Nevertheless, they firmly believed in their chance to reach the final against Bayern.

In case you missed it

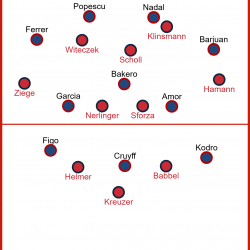

The starting lineups

Johan Cruyff sent his team out in its usual 4-3-3 formation. He had to make do without injured Pep Guardiola. Ferrer, Nadal, Popescu and Sergi Barjuán defended in front of goalkeeper Busquets. Bakero played in the holding midfielder position and Amor and Roger García in the two number eight positions. Luís Figo as the right winger, Jordi Cruyff as a fluid center-forward and Kodro as the nominal left-winger completed the first eleven.

Otto Rehhagel opted for a 3-5-2/3-6-1 formation. In front of Kahn, Babbel, Kreuzer, and Helmer formed the back three. Regular holding midfielder Matthäus was out with an injury. Hamann, Sforza, Nerlinger, and Ziege made up the four men midfield. Ziege took care of Figo in man-marking, which at times led him to fall back in between the back line. Scholl in the playmaker position was given a lot of freedom behind the two strikers Klinsmann and Witeczek. Off the ball, Bayern switched to a 2-1 formation in attack with Scholl in the inside right and Witeczek in the inside left channel supporting the One-Man-Pressing-Army Klinsmann.

The first half

Bayern started focused and pressed aggressively, suffocating Barcelona’s build-up play from the outset. However, after winning the ball, Bayern failed to capitalize on their chances on the break, often quickly turning the ball back over to Barcelona. It took until the 16th minute before Kodro, whom Babbel had a hard time containing in the beginning, had the first significant chance of the game after a nice interchange by Figo and Cruyff.

The teams largely neutralised each other. Barça built up patiently with almost all balls in the first and second third going through Popescu and Bakero. Bayern largely left this area vacated in favour of more compactness in the final third. Ziege had the first chance for the visitors in the 23rd minute after Kahn had initiated a swift counterattack, but his chip ball went over the goal.

Barça regularly overloaded the right wing. So too in the 39th minute when Figo and Ferrer managed to push through there after a beautiful piece of combinational play. Hamann intercepted the cross and two touches later the ball had got to Witeczek, who had dropped back into the central playmaker space. From there he played the ball back out into the open space behind the advanced Figo and Ferrer on the right wing. Mehmet Scholl received the ball and pushed inwards past Nadal straight along the horizontal line of the penalty area, from where he took a shot on goal in best Arjen Robben fashion. Busquets managed to block the shot, but the deflection brought the ball to the lurking Babbel who had a tap-in for Bayern’s opening goal.

Barcelona were shocked by suddenly falling behind and were happy to hear the half-time whistle not long after.

The second half

Bayern’s lead was deceptive. If Barcelona were to get just one goal back, they would win the tie. Knowing this, the Catalans remained patient – or unimaginative, depending on your point of view – in the second half. Again and again, Bakero and Popescu moved the ball forward without finding the final pass to create an actual goal threat. The only player Bayern never managed to get completely under control was Luis Figo. In the 56th minute he dribbled past Ziege and cut the ball back to Bakero from the goal line. Bakero’s subsequent shot over the goal was Barcelona’s greatest chance of the game up to that point. But in the following, Bayern remained focused and still allowed almost nothing. A blocked shot by Nadal from 35 metres out was indicative of Barcelona’s desperation.

The game lasted for 83 minutes before it fell to the ever busy Figo to create another chance for Barcelona with an individual action. He got past Nerlinger, Ziege and Helmer in midfield and tried his luck with a shot from 40 metres out which Kreuzer managed to block. The rebound got to Scholl, who immediately passed it on to Witeczek. Barça’s defensive efforts were again poor, which allowed Witeczek to break away undefended 30 meters towards Barcelona’s goal. Nadal hesitated too long, was unable to close down Witeczek in time and his late challenge only put a slight deflection on Witeczeck’s shot. The shot caught Busquets on the wrong foot and so it went in for Bayern’s second goal.

Barcelona now needed two goals to reach extra time and three goals to get to the final outright. This was not meant to happen. In the 88th minute, a free-kick by de la Peña from the corner of the penalty area reduced Barcelona’s deficit to 2-1. The ball took a deflection by Hamann substitute Strunz which made it unstoppable. After 92 minutes, referee Atanas Ouzounov blew the final whistle and FC Bayern had reached the UEFA Cup final for the first time in the club’s history.

Things I noticed

1. Lionel Scholli and Xabi Sforza

Many Bayern players deserved special praise, but two stood out in particular. Mehmet Scholl needed some time to get started before he found his way into the game. Before Babbel’s opening goal, there was not much to see of him in the first half. But this was about to change completely in the second half. Scholl was a permanent source of trouble. He did not only initiate both goals, he also managed to create further chances and had a number of shots himself. If Opta statistics had already been around at the time, they would probably have recorded about ten successful dribbles, five chances created, three goals scored and two attempts on goal.

Quite a few of Scholl’s actions were the result of a switch of the play by Ciriaco Sforza after he had successfully won the ball. Rehhagel liked to compare Sforza’s role to that of a quarterback in American football. Positioned in defensive midfield in front of the back line, he should read the game, secure the ball, and initiate his team’s build-up play. Against Barcelona, he did so brilliantly. In the beginning, he frequently dropped between Bayern’s defenders to cancel out Barcelona’s pressing. Later in the game, he was a calming presence in midfield and marshaled his young teammates around him. He also judiciously decided when to speed up the game and when to calm things down.

2. High tactical level on both sides

Given that the game took place more than 20 years ago, there was a surprisingly modern football on display from both teams. It is impressive how much of Cruyff’s handwriting of the time is still present in Barcelona’s game today. Cruyff’s build-up play was based on countless little passes and a lot of touches in central defensive midfield. When in the game Barça created overloads on the right side, Kodro moved from left wing to the center of attack, and Jordi Cruyff shifted out to the right or dropped in the central playmaker position as a false nine. This asymmetric shape gave Sergi plenty of room on the left wing, where he was usually on his own and used the available space no less offensively than Dani Alves or Jordi Alba would be doing 15 years later.

It was this iteration of Barcelona created by Cruyff that Pep Guardiola later build his teams upon. Five years prior Cruyff gave the 19 year old Guardiola his first minutes in La Liga and then made him his deputy on the field.

Bayern also played a modern brand of football that was ahead of its time in some respects. Phases of a high offensive pressing alternated with phases in which Barça was given more time and space. After winning the ball, Bayern sometimes transitioned very quickly from defense to offense, but sometimes also were clever enough to keep the ball in possession for several consecutive minutes. The back line, in particular, almost never took to long balls up front, but always tried to build up through a controlled combinational play.

However, it would not have been the nineties and the coach would not have been Otto Rehhagel if these modern touches had not been complemented with classic man marking, something that is rarely seen today. So Ziege never left the side of Figo, even when the Portuguese switched sides from right to left.

3. Landmark victory cannot save Rehagel

Otto Rehhagel commented on the victory with the words: “This is a historic victory for Bayern and a historic day for me.” A reasonable assessment of the game. Bayern’s last participation in a European final had been nine years ago, the last international title even 20 years ago.

However, reaching the final was not enough for Rehagel to save his job. He had been under fire for most of the season already, and after a home defeat against Rostock, he was finally released just before the final. Mehmet Scholl, for example, had criticised months earlier: “The fact is, we’ve been playing for eight weeks and still have no tactics. We are only in such a good position because we have so much individual quality in our squad.” President Franz Beckenbauer took over as interim coach and, not long after, led his side to a triumph in the UEFA Cup, which he had once dubbed the “Cup of the Losers.”

Significance for the club and its future development

The two legs of the UEFA Cup final against Girondins Bordeaux should turn out to be no more than a mere formality. Gernot Rohr’s team, which contained the later world cup winners Zidane, Lizarazu and Dugarry was not much more than a bystander in the glorious victory of Bayern. In the first leg in the sold-out Olympiastadion Bayern won with 2:0, goals scored by Thomas Helmer and Mehmet Scholl. Scholl scored again for the 1:0 in the return leg in Bordeaux. Kostadinow made it 2:0, before Dutuel scored for the French. Jürgen Klinsmann put the game away with his 3:1. It was Klinsmann’s 15th goal in the UEFA Cup that season, setting a new record. He was the first player since Rummenigge to score more than 30 goals in a season as a Bayern player.

The triumph completed Bayern’s title collection: FC Bayern were the third club in Europe to win the three major cup competitions, following in the footsteps of Ajax Amsterdam and Juventus Turin.

At an eminently important time, FC Bayern’s title was a statement that was heard around Europe and meant their ascent to the European elite. The Bosman ruling and the Champions League subsequently accelerated the globalization and commercialization of football, with FC Bayern leading the way.