Game Of My Life #09: A highlight of German football

This article was written by Constantin.

What the game meant

However, reaching the final did not equal the peak of either teams’ development. As accomplished as their football already was at the time, both clubs would go on to have many more quite memorable encounters in the following years. FC Bayern profited greatly from the intellectual input from Pep Guardiola, who tried to maintain the pragmatic and successful playing style that Jupp Heynckes had established while taking it to a higher level at the same time. Meanwhile, Dortmund was in a situation not quite of their own choosing that season after season they had to be creative to compensate for some of their most important players leaving. They were fortunate that Jürgen Klopp did not just have a sense for high-octane football, but also a knack for trying out players in positions to which they were not at all accustomed. Despite having suffered plenty of defeats and disappointments in the first half of the 2014/15 season, the team was far stronger than their points tally suggested.

(Image: Adam Pretty/Bongarts/Getty Images)

And so on 1 November, 2014, two teams met in the Allianz Arena who were about to deliver a full 90 minutes of the best football ever to have been staged in a German stadium. As an observer, one is not always able to fully grasp the special significance of an event while it is taking place. Retrospectively, however, in light of the disappointing turn German football has taken in the years since, the full extent of quite how extraordinary the game was becomes clear.

Guardiola’s fear of counterattacking football

When Pep Guardiola arrived in the Bundesliga, he had already studied German football intensively. He had spent his year-long sabbatical not just frequenting New York coffee shops, but mainly studying German football on TV and on location. The Catalan was so impressed with, and in awe of, the quality of counterattacking football on display in the Bundesliga that he immediately started to contemplate how he would have to organize a defense and midfield to evade the pressing traps the German teams so often deployed in order to launch a counterattack. He nurtured, reassessed and fine-tuned his ideas until that famed match in November of 2014.

In case you missed it

The starting lineups

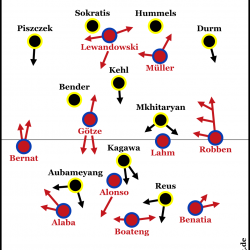

Bayern started the game in a 3-1-4-2 formation with quite a few interesting player positionings. Most notably, there was David Alaba at left center-back, Jérôme Boateng at central center-back, Xabi Alonso as a holding midfielder dropping in between the center-backs, Mario Götze and Philipp Lahm as the two number eights, and Arjen Robben as the right winger. This system was Guardiola through and through.

They faced a Dortmund side that Jürgen Klopp had assembled no less creatively. Their starting formation was a 4-3-1-2/4-3-3 with the following assignments: Sven Bender was the right number eight next to Sebastian Kehl. Henrikh Mkhitaryan was the more offensive second number eight on the left. Center-forward Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang had a loose role that saw him drift out to the right wing frequently. This conversely applied to Marco Reus as his counterpart on the left. Shinji Kagawa was positioned slightly behind the two in the center as a false nine. Incidentally, up to this point Kagawa had never lost a game against Bayern throughout his entire career. This was about to change very soon.

Give the ball to Alonso

The match demonstrated once again (and probably even more so than most) the lengths Guardiola had to go to in cancelling out the opposition’s pressing in order to maintain his high share of ball possession. Dortmund defended very high up the field in their 4-3-3 formation, effectively almost entirely suffocating all room for manoeuvre of Bayern’s defenders and midfielders. Thus, by way of a tight man marking in combination with the high intensity that is so characteristic of Klopp teams, they managed to almost entirely suppress any advance by a Bayern player past the half-way line.

While at Bayern, Guardiola always used to be looking for a way that allowed at least one of his players to rid himself of the tight marking of his opponents and get sufficient time on the ball to build up Bayern’s play. Often, this player was Boateng. In this game, however, the role fell to Xabi Alonso, who for practical reasons turned out to be the ideal candidate. The Spaniard simply dropped off slightly to move behind Dortmund’s first line of pressing, thus creating a numerical superiority close to his own goal. If he had stayed in his default position, Kagawa would have had an easy time marking him out of the game.

(Image: Adam Pretty/Bongarts/Getty Images)

Despite their man marking setup, Dortmund could not afford to change to a 4-2-4 and dispatch one of their midfielders up front to chase Alonso, because the team put too great an emphasis on stability and compactness in midfield. The method of Alonso dropping off, however, was anything but ideal for Bayern in other respects. Lahm and Götze could not make an impact in midfield. They were always outnumbered by the defensively skilled Bender and Mkhitaryan alongside holding midfielder Sebastian Kehl as an additional backup.

Nevertheless, Bayern did not suffer too many turnovers of possession. They were able to take on and overcome Dortmund’s initial pressing line with successful dribbles, which allowed them to push through to midfield and continue to build up their attacking game from there. But because Dortmund had the center firmly under control, Bayern was forced to play most passes to their wingers or another player who had shifted out wide before.

The battle of adaptations begins

The numerical superiority of Dortmund in midfield and Bayern’s aggressive gegenpressing through their midfield triangle, which was occasionally supported by one of their defenders stepping up, made for such an intense experience that it could have come straight out of a DFL advertisement. In those days the Bundesliga was the most spectacular league in the world if permanent end-to-end action with constant pressing and frequent transitions at breathtaking intensity is considered a spectacle.

On the one hand, the way the game developed was a blessing to Dortmund because it allowed them to keep in check the utterly relentless offensive machine that was Bayern and force them to seek a hasty finish repeatedly. Bayern also had to play down the flanks and through the half spaces with precision and pace if they wanted to avoid becoming involved in challenges at every turn. This, however, left them outnumbered in the center of the final third. Robert Lewandowski especially was completely isolated from his team’s attacking game most of the time and only managed to get his share of chances because, well, he is Robert Lewandowski.

On the other hand, the visitors had difficulties getting the ball through to their own attackers. Only rarely did they manage to break out of their compact shape in midfield and penetrate through Bayern’s non-stop gegenpressing. Reus and Aubameyang were almost completely cut-off in attack – and yet managed to score the opening goal by a collaborative effort in the 31st minute after a swift counterattack down the right flank when Aubameyang was able to capitalize on his enormous pace once again.

Now the wheels in Guardiola’s head started turning. For half an hour he had patiently witnessed what had been going on and now he decided that it was about time he had reigned in Dortmund’s attacking prowess. He ordered David Alaba and Mehdi Benatia to move higher up the pitch and cover the space behind Juan Bernat and Arjen Robben. This allowed Xabi Alonso to push up into midfield after the initial build-up phase instead of dropping off, thus in turn allowing Lahm and Götze to push up along with him. Boateng commonly was the only one staying behind as the last resort in defense. Guardiola was convinced that his gegenpressing would do the job and nip any Dortmund attack in the bud.

Klopp in the meantime was not one for dawdling either. He happily accepted the challenge by his Catalan counterpart and joined in the fun of moving around the imaginary tactical football chess pieces on the field. Little by little, Dortmund’s 4-3-1-2 morphed to a 4-4-2 as Klopp attempted to strengthen his defense on the wings to counter Alaba’s and Benatia’s repositioning. By the same token, however, he more or less sacrificed Dortmund’s high pressing since neither Reus nor Aubameyang were any more able to exert the same kind of pressure on Bayern’s build-up play as in the game’s early stages. As a result, Boateng and Alonso now had considerably more time to build up from the back, which they used to split open Dortmund’s defense with increasing precision. Dortmund’s only rescue was the commanding presence of Bender and Kehl in holding midfield which kept their defense from falling apart against Bayern’s constant barrage of attacks.

Smooth operator Ribéry

Both teams’ substitutions in the second half underlined once more the different strategic approach both sides took to the match. Dortmund, being one goal up, wanted to maintain their defensive stability as well as they could. Hence, Klopp brought on the physical Kevin Großkreutz for the technical Shinji Kagawa in order to strengthen his team’s running capacity in defense in their 4-4-2 formation with fresh energy from the bench. Guardiola, by contrast, made a completely different move: Franck Ribéry came on for Mario Götze and, unlike Thomas Müller, who now went out to the right side, quickly turned into a nightmare for Neven Subotić. Ribéry kept on attacking the Serbian ceaselessly and harassed him so vehemently that he was forced into making mistakes over and over again. That he could not hope for much help from his teammates, who were busy defending Lewandowski and Robben, only served to exacerbate things.

(Image: Adam Pretty/Bongarts/Getty Images)

Should Klopp have reacted by switching to a back five in this situation? Perhaps. Matthias Ginter could have provided some much needed opposition to Franck Ribéry in the defensive half spaces. Bender could have dropped off situationally as well. But it had not been the first time that Dortmund seemed to consciously submit to their fate with open eyes in the final minutes of a match against Bayern. And so it happened what was bound to happen. First Lewandowski scored the equalizer after a mistimed tackle from Subotić, then Robben secured the victory by converting a penalty kick not long after. The foul for the penalty was committed by Subotić against a Ribéry in afterburner mode. The defeat meant another setback for a troubled Dortmund side that had fought bravely but was unable to come away from the match with anything countable to improve their precarious position in the table.

An evening for the history books

Bayern and Dortmund have had so many remarkable encounters over the years that it is sometimes difficult to tell them apart. Of course, there were the epic battles in the Champions League and the DFB-Pokal finals, but also many smaller, “ordinary” contests in the Bundesliga, many of which have an interesting story to tell in their own right. Just think back to the counterattacking Dortmund victory in 2014, Götze’s goal in the Westfalenstadion, the penalty debacle in the DFB-Pokal, the humiliations for Tuchel and Favre in the Allianz Arena.

For me, this match in 2014 represents the high water mark of all of these encounters. In the run-up to it, the match might not have received the usual attention due to the table situation of both clubs. On the surface, Dortmund seemed to be in the middle of an identity crisis, but on the evidence of this match this was clearly not the case. They still played vintage Klopp football – only executed with limited means. Guardiola’s Bayern, on the other hand, performed at the peak of their potential, a state that should not last until the following spring, much to their chagrin.