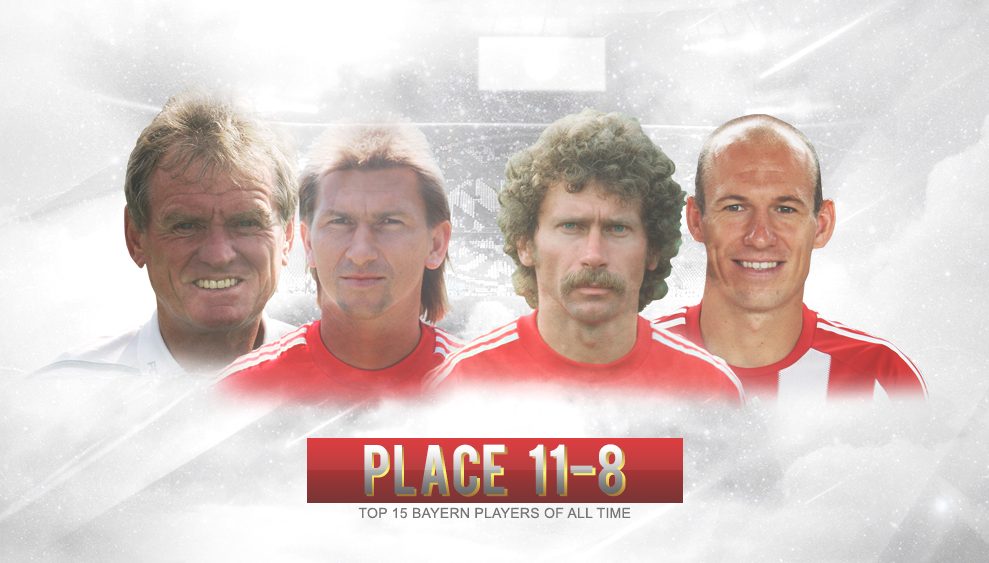

Miasanrot Awards: Place 11-8

11th place: Sepp Maier

by Maurice Hauß

Germany has always been the nation of the great goalkeepers, who often had to fight for a place in the national team. In the 1970s, perhaps the most successful period of German football, there was one undisputed goalkeeper: Sepp Maier.

There are countless anecdotes about Sepp Maier. For example, how he actually wanted to become a striker and then of all things was ordered into goal by the coach in a match against the youth of FC Bayern because the regular keeper had injured himself. Or how he was chasing a duck in May 1976 from a dangerous mixture of boredom and exuberance in the game against Bochum. Or how he and the sports supplier Reusch laid the foundations for the modern goalkeeper gloves.

Indeed, Maier was more than just a goalkeeper. Even off the pitch, the native of Lower Bavaria was a joker, from whom even today Thomas Müller or Franck Ribéry could not be safe. After all, the young Sepp wanted to become an actor and also tried his hand as a double of the Munich comedian Karl Valentin.

But on the pitch Maier was always dead serious. The national player was ambitious and was able to put his front men in their places if necessary.

His goalkeeping made him world famous. The Katze von Anzing, as he was called after his former gymnastic training and his graceful movements, had his strengths on the line and in positional play, but also in controlling the penalty area. Maier’s goal was not just to punch away balls, but to catch them.

He said, “If you’re in the right position, you don’t have to fly” and “As a goalkeeper you have to be calm, but you have to be careful not to fall asleep”. Maier was never a penalty killer during his career, as he never gets tired of emphasizing in interviews these days.

Until today Maier is record player of FC Bayern with 472 league games. Unforgotten also his series of 442 matches, which he played in a row and without exception. With 95 international matches, he is still the goalkeeper with the most matches for the national team.

Together with Beckenbauer and Müller, he formed the legendary Bayern axis, which won numerous titles for the club and the national team at the beginning of the 1970s. Maier won four championships, four cups, four European cups, one European Championship and the World Cup in his home country.

Germany’s goalkeeper of the century is no stranger internationally either. In his election for World Goalkeeper of the Century, he took fourth place behind Lev Yashin (Russia), Gordon Banks (England) and Dino Zoff (Italy).

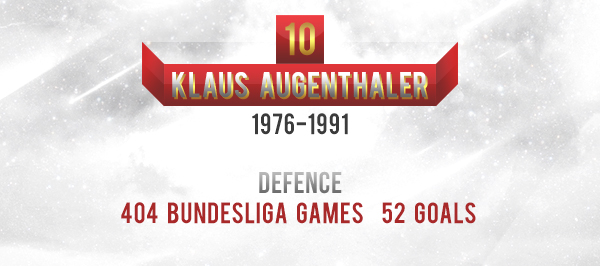

10th place: Klaus Augenthaler

by Maurice Hauß

In the summer of 1975, a 17-year-old picture-book Bavarian, as he was so often affectionately called later on, joined FC Bayern’s youth team. The young Klaus Augenthaler moves from his home club FC Vilshofen in the Bavarian forest to the metropolis of Munich. A big step for the trained central defender. In Munich, Augenthaler took the path “from suitcase carrier to boss”, as his long-time companion Dieter Hoeneß once put it.

Under Gyula Lóránt, “Auge” was integrated into the first team as Libero and played his first Bundesliga game against Dortmund in 1977. Until 1991 he played a total of 546 matches for the Munich team, the fourth most for a Bavarian player and even the second most for a field player. For his trophy cabinet, the Bavarian collected seven German championships, three cup victories and crowned his career in 1990 with the World Cup. He also reached the final of the European Champions Cup in 1982 and 1987.

As a defender, Augenthaler was known for his powerful shot. He also scored his first goal of the season in his first match against Dortmund. Throughout his career he scored at least one goal each season as a defender.

A particularly spectacular goal will always be associated with Augenthaler. In August 1989 he was able to overcome Uli Stein in the Eintracht Frankfurt goal with his feared long-range shot from almost fifty metres in the DFB Pokal. The goal was not only goal of the month, but also goal of the year 1989 and goal of the decade of the 1980s.

The story of Augenthaler, however, cannot be told without a foul with no sending-off and a Watschn (a slap) with a back story.

In November 1985, the top duel in the German football between Werder Bremen and Bayern Munich took place. On the 16th matchday, Werder traveled to the Olympic Stadium as league leader three points ahead of Bayern. But after half an hour the game becomes insignificant.

Bayern are leading 1-0 at the time when Bremen’s striker Rudi Völler dribbles his way through Munich’s defence. Until he meets Augenthaler. The libero knows what’s at stake. Bayern can’t afford to equal the score. He brutally knocks down Völler. The latter has to be taken off the pitch injured, and is sidelined for a total of five months with an adductor rupture in the thigh. Augenthaler only sees a yellow card.

The picture of the Völler flying through the air goes through the entire country. After the game the reactions rain down on Augenthaler. The relationship between Bremen and Bayern noticeably cools down. The choice of words is hard. Bremen’s coach Rehagel speaks of a “hunt” on his players, Völler speaks of a “sign of shame by FC Bayern”, while Bayern coach Lattek – “We don’t play chess” – and manager Hoeneß – “a normal foul” – take the side of their defender.

Nevertheless, for a few months Augenthaler becomes the personified enemy of the Bayern haters. In the SportBild he says: “I would never have thought it possible what poured down on me afterwards. A real Bayern hatred broke out, I received death threats at the time, Bavaria had two security guards on duty who were sitting in the team bus with us.

The foul was the turning point in the championship. Bavaria won 3:1 against Völler-less Bremen. The return match in May 1986 became the comeback game of the Werder striker and goes down in history thanks to the legendary Kutzop penalty kick, which was won by Völler. FC Bayern finally became German champion thanks to the better goal ratio.

The duels with Real Madrid in the 1980s are particularly present in the biography of the Libero. If you ask Augenthaler directly, he would refer to the year 1980 as the starting point for this special relationship. In the preseason, the Munich team defeated star-studded Madrid in a friendly with 9:1, almost destroying them. In the following year, the Spaniards were looking for revenge and went after Bayern very hard in a preparation tournament.

When the European Cup duel took place in spring 1987, the stakes were correspondingly high. Bayern convincingly won the first leg at home 4-1. A gesture from Auge after a kick in the back by Hierro became famous. On his knees, the defensive leader indicated bull horns with two hands. What was supposed to mean that this game was not a bullfight, was considered an affront in Madrid.

The return match in the Santiago Bernabéu stadium becomes a gauntlet run for Augenthaler. In a heated atmosphere, he commits an own goal early on. After thirty minutes, Real star Hugo Sanchez fouled him hard. Too much for the otherwise calm and level-headed defender, who handed out a Bavarian Watschn to the Mexican.

The referee sent Auge off the field. The national player has to sit in the cabin for the remaining hour. In order not to notice anything happening on the field, he lets the shower run. It seems to help. Even without their defensive anchor, it remains the 0-1 defeat and Bayern advance to the final.

His deep attachment to FC Bayern was particularly evident after the end of his active career. Five years after his career ended, Augenthaler, who was assistant coach of the professional team at the time, played for the reserves in the fourth division four more times at the age of 39.

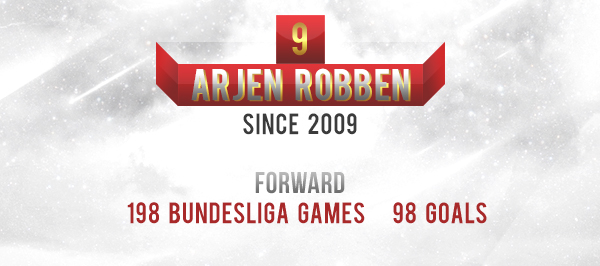

9th place: Arjen Robben

by Justin Kraft

I dreamed about you. About that Wembley night. And that was in 2012, when I slowly started to get up again and football returned to my life. It’s completely irrational compared to more important things in life, but after that defeat in the Allianz Arena against Chelsea in the Champions League final, I lost the desire for sport.

Arjen Robben represented this phase of emptiness. A shining professional. Someone who doesn’t pretend that the club he’s playing for is his childhood heart’s club. One of the professionals whose words carry weight. When Robben’s career began at a young age at Groningen and later opened the big door to England, that was the logical consequence of hard work. He always appreciated the colours of each jersey. But what mattered most was what was most valuable to his development.

In 2009 that was a clear step backwards. From the great Real Madrid, the star switched to FC Bayern, who had disappeared into insignificance in Europe. He immediately shot the Reds to the double and the final of the Champions League. But the last step was not taken. He also brought the Dutch national team into the World Cup final together with Wesley Sneijder. But the last step was not successful.

Then followed difficult years. Robben continued to fight tirelessly. His boundless talent brought him into the professional business. But it was his character and professionalism that made him a world star. Robben remained patient despite the setbacks and took responsibility.

In 2012, he led FC Bayern back into a promising starting position. But the last step was not taken. Missed penalty kicks in Dortmund and against Chelsea – the story is well known. And while I lost faith in justice in football in the following weeks, Robben stood up once more and wiped his mouth off.

He felt from the very first practice session that great things were possible in 2013, he said in an interview with us. Again the footballer and human Arjen Robben developed further. He became even better, even more professional and even more helpful to the team. Robben became a leader and role model. He led his team to the Bundesliga title and to the finals of the DFB Pokal and the Champions League. And the last step?

It was successful. Robben was perhaps the one protagonist to whom this heroic story can best be tailored. But he doesn’t want to know anything about it himself. It was above all the team that achieved this. The fact that Robben became a superstar is due to the nature of the story, which would probably have looked different in many places without this final.

But not with me. Robben’s character, his class and his manner made possible the enormous success that FC Bayern would probably not have had without him. Robben embodies what is often called the Bayern gene in Munich. And when I dreamed of it in 2012, of this Wembley night. There was no better scenario than to see the cheering Robben with the trophy in his hands. It’s all the nicer that Arjen did it!

8th place: Paul Breitner

by Tobias Günther

Paul Breitner’s career at FC Bayern is divided in two by the turning point of his move to Real Madrid following the 1974 World Cup. From 1970-74 he played as a left defender, but in 1978-83 he was the undisputed director in the central midfield. In fact, Breitner’s role in these two phases was far less different than it might appear at first glance.

The fact that skilled (wing) attackers are being transformed into full-backs is an everyday phenomenon today; however, at a time when man orientations were omnipresent on the pitch and a left defender was primarily one of three man-markers, this was still a peculiarity. Although Breitner was by no means the first “offensive defender” in football history, he interpreted this role in a way that set him apart from other full-backs and made him the (supposed) prototype of a “modern” defender.

On the one hand, he did his defensive work extremely disciplined and diligently; unlike, for example, some Brazilian backs with a pronounced offensive urge, Breitner’s defensive work hardly suffered from his excursions to the front. On the other hand, he was not a typical linear full-back running up and down the line. On his advance, Breitner moved towards the centre very early, often already in his own half. His goal was not necessarily to break through to the touchline to take crosses, but rather to play a creative role in the build-up of the game. An interpretation of the role of the full-back, as Marcelo’s recent Real Madrid performance was.

The Bayern team of the 1970s (and not least the national team) profited so much from Breitner’s abilities because he was able to step in when Beckenbauer, as director and creator of the game, was not able to make his mark. At the beginning of the 70s, many Bundesliga clubs were increasingly relying on Beckenbauer to be taken out of the game by a kind of special guard when he crossed the midline. With Breitner as an always available alternative, it was extremely difficult, especially for destructively acting opponents, to bring the Munich build-up game to a standstill.

In this respect, it becomes clear why Breitner’s move to the midfield centre did not represent a big leap for him (as it was not one for Lahm and even a Marcelo could easily master such a change of position). A large part of Breitner’s playing style could also be used as a midfielder virtually unchanged, which made him a kind of box-to-box director. As strong as ever in duels, he conquered the balls in defence, carried them with dynamic runs to the opponent’s penalty area and then distributed them with precise passes when, when he did not use his extremely dangerous distance shoot.

This versatility made him a kind of “do-it-all” when he returned to FC Bayern in a largely leaderless and headless team in 1978. However, Breitner was also dependent on an intact physique with his dynamic runs. He was not a director who could also steer a game as a “standing soccer player”, as Riquelme later celebrated. Therefore the period of the “Breitnigge”-duo was a peak, that unfortunately lasted only relatively short. Already in the season 1981/82 Breitner had to fight with injuries again and again, was consequently not in form after his DFB comeback at the WM 82 and had to end his career prematurely in 1983 with only 31 years.

In Germany, the footballer Breitner has fallen a little into oblivion, mainly he is perceived as a bitchy ex-professional, who likes himself a bit too much in his ostentatious out of the box thinking pose. This does not do justice to the player. After all, Diego Maradona, for example, risked the quarrel with his former club FC Barcelona only to be able to take part in the farewell game of his great idol.

Mainly perceived abroad as a revolutionary offensive defender, Breitner has continued to shape the image of a driving force and leading wolf in midfield in Germany to this day, as well as that of Uli Hoeneß as an ideal number 10. His successors in the FCB as well as in the national team (e.g. Lothar Matthäus) were continuously exposed to comparisons, especially regarding their leadership skills and presence in decisive games. But it would be wrong to reduce Breitner only to these secondary virtues.