Interview with Hoeneß biographer Günter Klein: “He thought the club would fall apart without him.”

We are delighted to be able to win over Günter Klein for an interview on this topic. The journalist is the senior sports reporter at the “Münchener Merkur” and in 2014, he co-authored the book “Hoeneß: the biography” with “AZ” journalist Patrick Strasser. The book covers the career of Hoeneß up to his (temporary) fall from grace because of tax fraud.

As soon as the AGM is over, Uli Hoeneß will no longer be part of Bayern’s senior management after almost 50 years of serving the club as player, manager, and president. Günter, is it at all possible to imagine an FC Bayern without Uli Hoeneß at the helm?

It is because a corporation with a yearly revenue of 700 million Euros is not dependent on one person, but on a functioning organizational structure.

Let us take a look back at the beginning of his playing career: in 1970, Uli Hoeneß joined Bayern having come from Ulm. What was his role in a team studded with stars like Beckenbauer, Müller, and Maier?

Before joining Bayern, he had already stood out as a talent in Germany’s youth national team. Back then, when the clubs did not have access to international players as easily as today, this was a real calling card and a ticket to professional senior football. Opinions vary as to whether he was a midfielder or a striker. For me, he was an incredibly quick offensive midfielder. Both Hoeneß and Breitner made an impact at Bayern right from the start.

He suffered a severe knee injury when he was only 23 years old. An injury that ruled him out for a long time, saw him lose his place in the starting eleven, and eventually ended his career as a player. Is the unfinished playing career of the 35 time German international one of the biggest “what if?”-stories in German football?

He was very fortunate to already have won almost everything there was to win at this point: European championship in 1972, World championship in 1974, several European titles with his club including his spectacular two goals against Dresden, which were the talk of the town all across Germany at the time. So there were not a lot of titles left for him to win. But it is always a tragedy, of course, if one loses the ability to do what they can do best, which has elevated them above everybody else, and if a life of constant competition that shapes one’s whole existence suddenly comes to an end.

“And then it was: ok, why don’t you do that?”

Straight after the end of his playing career, the still quite young European champion and World champion made the switch to becoming a manager in the sporting department of Bayern. How do we have to picture this transition?

Simple: he took off his training clothes, left the pitch and moved to his new office. There was not something like a job profile at the time. They just said: go ahead, you will be fine. His area of responsibility included everything from planning the squad to hiring the coach to negotiating with sponsors.

How did the novice manager manage to get started in the business and make a name for himself?

By being a tough negotiator in his dealings with potential signings. And by painstakingly defining the identity for FC Bayern Munich that he wanted to shape the club’s public image.

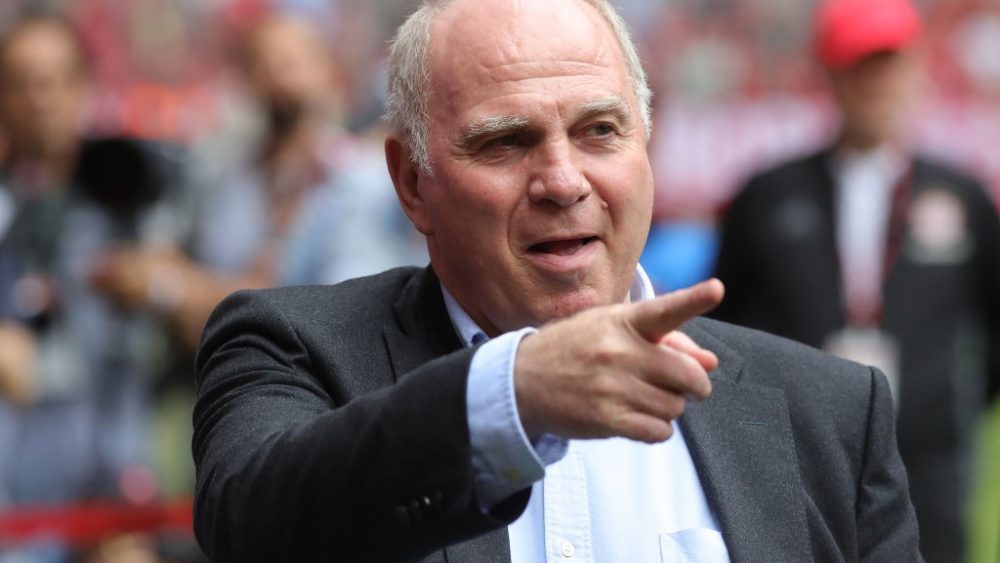

(Foto: Sandra Behne/Bongarts/Getty Images)

How much does the Uli Hoeneß of today have in common with the Uli Hoeneß of back then?

The similarities have become stronger again lately. The two are more similar now then they were a couple of years ago when Hoeneß seemed to have mellowed. These times are gone. Even though as a president he should not get involved in day-to-day operations, he rather acts like a manager most of the time.

Which people helped Hoeneß when he started out as a Manager and how many of these are still part of his inner circle?

Most of his close friends from back then, such as the entrepreneur Rudi Houdek or his predecessor as Bayern’s manager, Robert Schwan, are dead. His relationship with Paul Breitner is broken. Maybe there is Edmund Stoiber, with whom he is in close contact since Stoiber wrote him a letter to console him after his missed penalty at the 1976 Euros in Belgrade.

“He didn’t want to leave the fate of Bayern to the hands of Karl-Heinz Rummenigge alone”

For long periods of his career, Hoeneß worked alongside Beckenbauer and Rummenigge, both of whom are club legends in their own right. How would you characterize his relationship to these two?

For a long time, he could not get over the fact that Beckenbauer had caused his removal from Germany’s first eleven after the 0-1 defeat against the GDR at the 1974 World Cup. Later he was annoyed with Beckenbauer’s private advertising engagements which violated Bayern’s good governance codex, and with his unpredictable comments in public. Hoeneß always felt superior to the junior Rummenigge. Despite all the frictions over the years, the situation never got out of hand and there have been phases of genuine cordiality and solidarity if one of the three was in need of help.

The relationship between Hoeneß and Rummenigge is especially interesting. Who took which role, officially and behind closed doors? Who made which decisions? How did authority in the club swing back and forth between the two over the years?

When Beckenbauer and Rummenigge joined the club’s management in the 1990s, Hoeneß’s power was dramatically reduced. He had to fight for many years to to regain his position as number one in the club. Beckenbauer did not really care about a lot of things, Rummenigge turned out to be a more sturdy contender. Hoeneß thought that he bonded better with the players than Rummenigge. But most decisions were taken in mutual agreement.

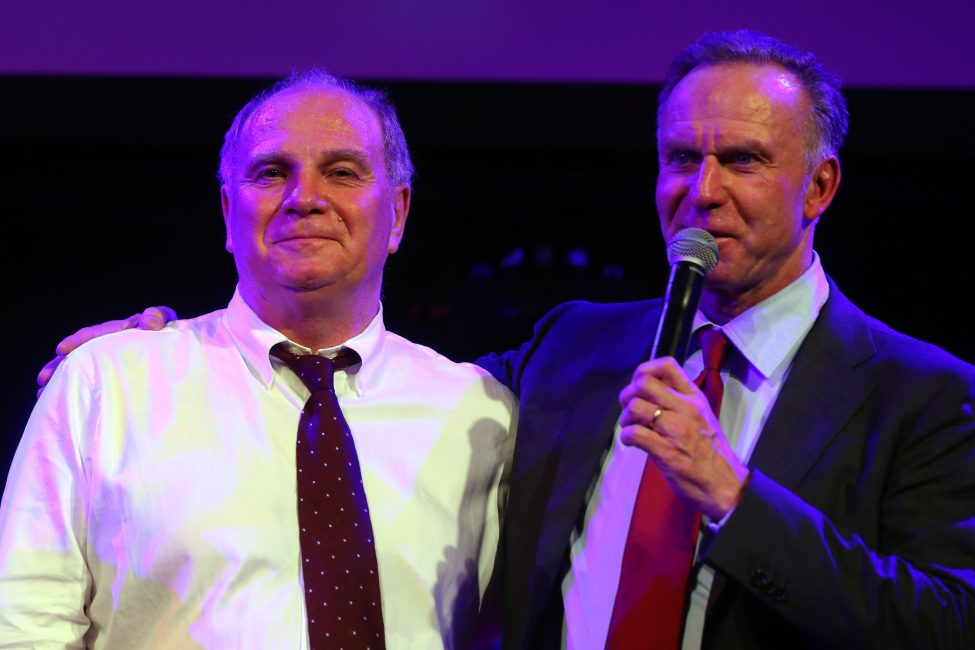

(Foto: Alexander Hassenstein/AFP/Getty Images)

Uli Hoeneß stated at the press conference where he announced his withdrawal that Rummenigge and he had had quite a few arguments in the past. Has their relationship always been tense? Have these tensions grown stronger in recent years?

According to Edmund Stoiber, the tensions have in fact become stronger recently. I think we can take him at his word. One of Hoeneß’s main motivations behind his return as president surely was that he did not want to leave the club all to Rummenigge alone.

Ottmar Hitzfeld once said: “Uli is an unconventional thinker. He thinks outside the box, differently from anybody else. He has a nose for business, he brings in the money.” Is this a good summary of Hoeneß’s personality?

It is a fitting description for most parts of his career. But the times have caught up with Hoeneß. He seems outdated now, out of touch with modernity. Other people have long started to quietly manage the club in the background. Moreover, he has lost his vision in recent years. But still, his visionary genius should be recognized first and foremost in recapitulating his long career.

Your book features a lot of quotes from Hoeneß. Which one describes him best as a person in your opinion?

The comic and satirist Django Asül once called him a blend of heart and elbow – this sums him up quite succinctly I think.

“It has to be possible to remain human”

Is there a fundamental principle that Hoeneß lives by? An ideal that guides his actions and his choices in life? What are Hoeneß’s strengths that have distinguished him over the course of his career.

That in any discussion or argument it should always be possible to reach a consensus based on the facts. This and his relentlessness in reaching a goal that he has set for himself. Take his transfers for example. Some of his major signings did not come to pass immediately but required a lot of stamina and insistence on his part.

Uli Hoeneß seems to have a talent to fall out with people. The list of his enemies is endless. Which of his numerous confrontations have left a permanent mark on him?

Those with Christoph Daum and Willi Lemke. Although the situation with Lemke has relaxed in the meantime. The argument with Daum, however, went to his core. Had Daum not been careless enough to agree to an examination of his hair for drug use – which more or less eliminated him from professional football for a number of years – Hoeneß would have become unsustainable at his position in the Bundesliga. His whole family lived and breathed the enmity with Daum. But they took note that Daum did not choose to retaliate when Hoeneß’s tax affair broke.

(Foto: Martin Rose/Bongarts/Getty Images)

The clash with Lemke was an organic result of the natural rivalry between the two most dominant Bundesliga clubs at the time. It did not leave any lasting scars on Hoeneß. At some point, the two just realized that they had a lot in common apart from differences in body shape and political orientation.

Van Gaal, Klinsmann, and lately Rummenigge. Could alpha male Hoeneß not countenance any other alpha males at his side?

Yes, I think that impression is justified. He probably feels flattered too that all these CEOs and top business leaders on Bayern’s board listen to him.

The year 2005 witnessed a most significant event for Bayern in the club’s history. Together with local rivals TSV 1860, the city of Munich and the state of Bavaria, FC Bayern laid the foundation of a new dedicated football stadium, the “Allianz Arena”. What part did Hoeneß play in all of this?

He was heavily involved and a real driving force behind the project because he recognized that Bayern would lose its competitiveness even with a renovated Olympia ground. Maybe he foresaw that 1860 would not be able to live up to their financial obligations in the long run. But he needed them as a partner to unlock the public subsidies needed for developing the area where the stadium was based, which was more expensive than the construction of the arena itself.

“Suddenly he could be seen in a suit and tie instead of a jumper”

When Hoeneß ended his reign as Bayern’s manager in 2009, another one of the dying breed of charismatic sporting directors like Calmund, Lemke, or Assauer, left. Has this role model of the all-powerful sporting director outlived its usefulness?

It has because the the requirements of this position have become far too complex for one person alone to handle. The sporting director has to coordinate and oversee the duties of a squad developer, a scout, and a team manager who makes all the necessary travel arrangements from organizing a tour bus to booking a hotel – but he does not have to do all of this by himself. A sporting director also does not have to know the entire European player market down to U13 level inside out.

“Hoeneß is not opposed to contrary opinion. He values being challenged.” Günter Klein about the collaboration of Sammer and Hoeneß.

One day, he suddenly turned up in a suit and tie and no longer wore jumpers. He ceased to sit in the dugout and strove to appear presidential.

His immediate successor as manager was – to many people’s surprise – Christian Nerlinger. Did he have the power to execute his job freely or was he rather a sock puppet of Hoeneß?

Nerlinger had the reputation of being a nice and cooperative guy, which, I believe, was part of the reason why he was appointed next to the complicated Jürgen Klinsmann as coach. I believe that Nerlinger actually was not completely powerless, but it seemed clear from the outset that the person immediately following Hoeneß in this position would have a very hard time.

Nerlinger had to step down following the defeat in the “Finale Dahoam” (final at home) and Matthias Sammer took his place. This seemed like a surprising decision again because Sammer had the reputation of being a strong-minded outside-the-box thinker. What were the causes of his appointment? And how would you characterize the working relationship between Hoeneß and Sammer?

Something had to change and Bayern did not want to sacrifice Jupp Heynckes. Heynckes was not too happy to learn about Sammer’s appointment. As surprising as the decision for Sammer might have appeared superficially, he and Bayern had a lot in common in truth. Sammer was living in Munich at the time and he was often seen at the Säbener Straße because he brought his son there for his PE lessons in school. He was also one of Bayern’s main DFB contacts, where he worked. Hoeneß is not opposed to contrary opinion. He values that.

“People cannot let go of power easily…”

When Sammer left Bayern for health reasons among other things, he was succeeded by Michael Reschke for a while before Salihamidžić got the job. So after 30 years of continuity, the appointment of Salihamidžić saw already the fourth man in charge within ten years. Is this a tribute to how increasingly short-term modern business has become or rather a case of Hoeneß’s shoes being to big to fill?

Bayern had fallen behind the times and the figure of Hoeneß had been so dominant there that the club did not realize the importance of hiring a sporting director and splitting up responsibilities. It has to be said though that neither Nerlinger, Reschke, nor Salihamidžić are the kind of person that would instantly rally a huge following around them. Reschke in particular was not taken seriously as a person at all.

Why did it take so long for the club to acknowledge the need to split up and distribute the sporting responsibilities to several people in ernest? And why did they eventually settle for an old hand from the 2001 team (Salihamidžić)?

Power is something people find difficult to let go of. The club also had to make compromises for the job. Hoeneß did not want an outsider like Jan-Christian Dreesen or Jörg Wacker to rule over the future of the club, even though they are quite good at what they do there. Hoeneß wanted to avoid a certain sense of facelessness and lack of club identity in management.

(Foto: Lennart Preiss/Bongarts/Getty Images)

Hoeneß’s career collapses like a house of cards in 2013. The suspicion that he might have cheated with his taxes becomes public knowledge. He is found guilty of tax fraud in March 2014. He begins his sentence in June 2014. His conviction marks the steep fall from grace of a seemingly infallible icon of German football. How has Hoeneß’s tax affair affected his public perception in footballing circles in retrospect?

Crucially so. Before this incident, most people had made their peace with him. He stood for a club that nobody liked, but people respected his unconditional identification with FC Bayern, his engagement for good causes, and they liked his outspokenness and the way he did not beat around the bush in TV talk shows. All of this sometimes grudging affection was gone in an instant. One had to be fairly delusional to come up with any form of justification for what he had done.

Do you believe Hoeneß when he says that he initially had not planned on making a comeback as president after his time in prison, but was persuaded by the public appeals of the fans?

I do not. I know from a confidant of his that he believed that the club would fall apart without him.

Hoeneß is released early from prison at the beginning of 2016. In November of the same year, he stands for president at the AGM and is elected. Is there any difference in the way he has carried out his duties before and after his time in prison?

Before his time in prison, he was a ‘presidential’ president. He took care of the club as a whole. After his return, it was all about football and basketball for him, the club’s day-to-day operations, managing the business side of the corporation – all of which technically was not part of his remit as president. But he was back to being the manager.

In his last stint as president, Hoeneß sometimes appeared angry and unforgiving. He insulted Özil and Bernat with very harsh and mean remarks, for example. Where do you see the reasons for his conduct?

He seems to have become a harder and more callous person while he was in prison. Maybe there is also a moment of bitterness at the way his life has taken.

“Before this incident, most people had made their peace with him. He was shown a lot of respect by many people. All of this was gone in an instant when his tax affair became public knowledge.” Günter Klein, about the public image of Hoeneß after his tax affair.

Do you believe Hoeneß when he says that he is stepping down now because he considers the club to be in a good position for the future and the question of his succession suitably arranged? Or did the criticism he faced at last year’s AGM play a part in this too? Or has he maybe become estranged from the business of football in general as it is now?

The AGM played a big part in his decision. But he also did not take it well that not more of Bayern’s leading people jumped to his defense. Nevertheless, he has made all the necessary arrangements with regards to his succession that he deemed important.

“He has to be ranked first in the long line of FC Bayern luminaries”

Now Hoeneß is going to take a back seat role. Herbert Hainer is set to follow him as president and chairman, and Oliver Kahn will join Bayern’s management board at the beginning of next year to become the long-term successor to Karl-Heinz Rummenigge. In which condition does Hoeneß leave behind his lifetime’s work?

FC Bayern is more than well positioned for the future. The club has done a lot of things right, not least thanks to Uli Hoeneß. It is most unfortunate for the club that the face of international football has dramatically changed in recent years, so much in fact that it had been virtually impossible for the club to properly prepare for this. Bayern will therefore probably play a smaller role internationally in the years to come than the club deserves.

Hainer and Kahn were hired by Hoeneß as well, but they seem to be their own people with their own ideas. Will Bayern change its face in the coming years and slowly depart from Hoeneß’s ideas? Do they have to in fact?

That is difficult to predict. It will partly depend on the way international football will develop, which Bayern cannot completely escape. Will there be a super league? This would entail almost revolutionary changes to football in general – and to FC Bayern in its wake.

(Foto: Alexander Hassenstein/Bongarts/Getty Images)

What is your assessment of Hainer? How important will the club’s members be to him, a group of people whose opinions and sentiments Uli Hoeneß always valued very highly? And how will he deal with the club’s social responsibility and engagement for the public good, Hoeneß’s most defining territory?

Hainer is an unknown quantity for the casual follower of professional sports. I do not believe that many Bayern supporters had him on their radar. His connection to the club has mainly been seen as a business relationship, not so much as an emotional one. I still consider him an Adidas man first and foremost although he left the company three years ago already.

One final question: in your opinion, where does Hoeneß rank in the long line of all-time Bayern greats among such luminaries as Landauer, Neudecker, Schwan, Beckenbauer, and Rummenigge?

Well, you will have to say that he comes first.