When Sebastian Deisler made time stand still

1-0 down again. Deservedly so. So far it hasn’t been FC Bayern’s season, as they’re on their way to a fifth defeat of the season in November 2006 on a cold afternoon in Hamburg. Van der Vaart had put Thomas Doll’s HSV in front with a penalty in the first half. Bayern manager Felix Magath can’t have liked what he’s seen so far. Two changes as early as half-time. Lucio for Demichelis. Deisler for Ottl. Deisler? Then 26, he’d just come back from an 8-month lay-off. His fifth serious injury to his right knee had cost him participation in the World Cup in his home country. A week before, he’d celebrated his comeback against Stuttgart. For just a few seconds in added time, that is. Now Magath is giving him an entire half.

***

If you want to understand Sebastien Deisler’s story, you have to place yourself into a different era of football. When Deisler stepped onto the Bundesliga stage in 1998 at the age of 18, there was practically nobody like him. There were no young, talented German players in the Bundesliga. At the World Cup in France which had just come to a close, Jens Jeremies was the youngest player in the German squad. At 24. German football was still defined by a set of over-30s. Klinsmann, Bierhoff, Möller, Kohler – and yes, even Matthäus. Deisler was to suffer his first serious injury to his right knee in Mönchengladbach just a few months after his Bundesliga debut. A cruciate ligament injury saw him resigned to the sidelines for several months, starting October.

When Deisler sets the ball rolling for one of Gladbach’s few victories of the season with a run from his own half against 1860 Munich in the autumn of 1999 after his comeback, the hype has reached fever pitch.

Two years before that, he had already been voted second-best player of the tournament at the Under-17 World Cup in Egypt. Just behind Ronaldinho. The name’s ‘Basti Fantasti’ now. In one fell swoop, Deisler takes the role of German football’s golden boy from the now clearly more mature Mehmet Scholl, who doesn’t mind taking himself out of the limelight anyway. Technique, speed, brilliance. German football, in a time when players like Ronaldo or Zinedine Zidane define international football, is longing for these qualities. Because while others had Zidane or Ronaldo, Germany had Andy Möller and Jörg Heinrich. Within just months, Deisler is soon rated as the talent of the century.

Berlin as a “killer blow”

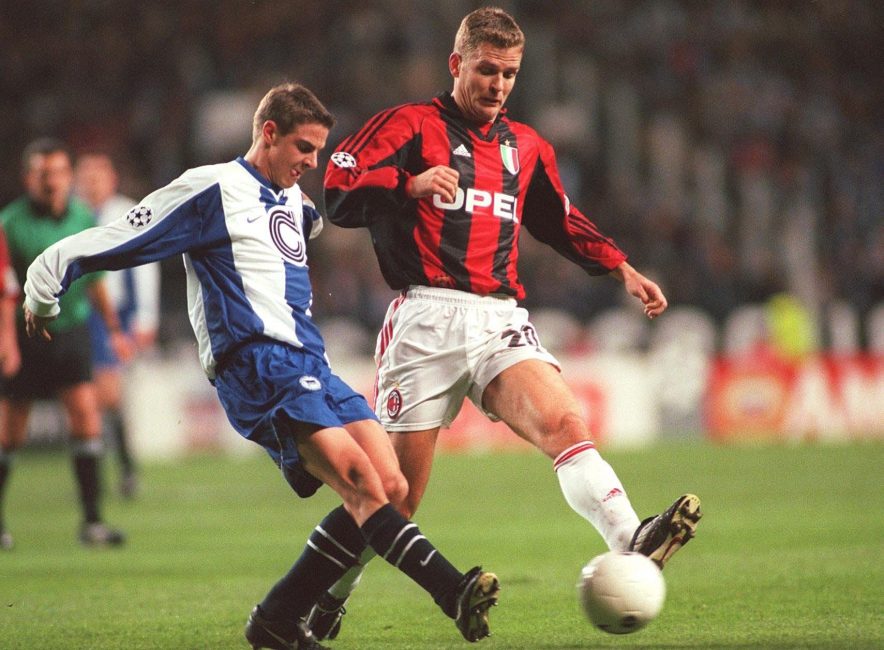

After Mönchengladbach are relegated, he decides to move to Berlin in 1999. Hertha had just surprisingly qualified for the Champions League. At first, it seems a smart, logical step in his career. He picks up in Berlin where he’d left off in Mönchengladbach. In his first three league games, he’s involved in four goals. Also, thanks to him Hertha make it through the group stages of the Champions League, beating AC Milan 1-0 at home. Deisler was playing well on the European stage too. It’s this mixture of tight ball control, surprising movement and genuine dynamism that makes Deisler’s game so electrifying in the early phases. And then you have the stunning set pieces, good shooting technique and excellent crosses. He’s seen abroad, too, as *the* German talent. Deisler feels in demand. In the spotlight. The attention flatters him, but he’s neither ready for it nor suited to the role of the star.

The next knee operation at the end of 1999 doesn’t stop him from taking part in the Euros in 2000. At 20, he’s by far the youngest player in an aging German squad. Michael Ballack, who had the opportunity to develop in Kaiserslauten and Leverkusen and was expected to define the national team, is at 24 the only other young pro who people held out hope for. In the tournament in the Netherlands and Belgium, which ends in the knock-out round for Germany, both play only a bit-part. Nobody realises that this will remain Deisler’s only big tournament.

Two years later, Deisler and Ballack move to Munich together. The big 2001 generation of Effenberg, Elber and co. has either already departed the club or are on their way out. What nobody knows at the time is that when Deisler arrives in Munich, in principle he’s already a deeply insecure, almost broken young man. Later, he would point to his last season in Berlin as the killer blow. “Today I know that I should have quit there and then,” he said in 2010 in one of his few interviews in die ZEIT. After a leak from a bank, Deisler’s planned move to Munich became public in the autumn of 2001. Supposedly, he’s set to pocket a signing fee of 20 million Marks. When this is made public, things go badly for him. Hertha manager Dieter Hoeneß had supposedly asked him not to go public with his transfer request. When the transfer then became public, Hoeneß doesn’t stand up for his player, and instead throws him under the bus. That’s how Deisler sees it anyway. Hoeneß refutes this representation.

From then on, Deisler is public enemy number one and is sent death threats, and completely shrinks back into his shell. And when he suffers another bad knee injury just days after the publication of his transfer, forcing him to miss several months, he can’t even prove himself on the pitch. Can’t show that he’ll fight for the club until the end. Instead, he sits in the stands with his crutches and is sworn at.

He wasn’t happy in Berlin in any case. In his biography “Back to Life” he describes how he tried to live the big life like the other stars. Cool cars and clubs. He tries to play along, and feels nothing. He felt like a sad clown in Berlin, he says later.

Deisler almost missed the 2002/03 season entirely, as he was badly injured again just before the 2002 World Cup. That right knee again. Consequently he had muscular problems in his thigh too. After that, things started looking up. At the beginning of the 2003/04 season, Hitzfeld relies on him. After his long break, Deisler finally seems in top shape. He’s lively again and has a positive influence on games. More and more, his dangerous crosses find Michael Ballack, incredibly strong in the air. On top of that, Deisler scores three times in the first 11 games. In the 4-1 against Dortmund in November 2003, he’s one of the best players on the pitch, registering two assists. Ten days later he was checked into hospital due to depression. The public are shocked by the news of Deisler’s depression, which only goes to show how far the perception of public figures can differ from reality. Anyone who understands Deisler’s story in his own words asks themselves in hindsight how he was even able to put up with it all for so long.

Right winger without freedom

From summer 2004, Felix Magath is the manager in Munich. Magath relies on pressure, almost insecurity, to get his players to perform. Deisler, who retrospectively reveals a playful, almost artistic, romantic view of football, doesn’t really fit that style of management. In spite of that, he battles. He’s hard with himself, wants to toughen up to finally fulfil those expectations which come along with his reputation and salary in Munich too. At the same time, he looks for joy in the game. That’s what keeps him in football for a time. Combining with the strikers who weave in front of him and open up gaps for his passes. The little moments.

Between 2004 and 2006, Deisler stays injury-free over a long period of time for the first time. Good games are rare for him in Munich though. Magath mostly subs him on late or off early. He can’t build any rhythm or trust in his knee. Things are a bit better with the national team. The new manager, Jürgen Klinsmann, makes clear early on that he’s saving a spot in the squad for Deisler for the World Cup of 2006. He makes 13 international appearances in 2005, including good performances in the Confederations Cup against Tunisia, Argentina and Brazil.

In Munich, Deisler plays almost exclusively as a right-winger. A bit like Bastian Schweinsteiger later, his qualities don’t really show there – not anymore, since by now he’s lost his explosiveness to his many knee injuries. He aspires to play in the middle, feeling restricted in his creativity and freedom a yard next to the flank, as he describes it later. During the title-winning seasons in 2005 and 2006, he’s degraded to the crossing and set-piece specialist on the right side.

He had already been regularly compared to David Beckham in his younger years. He actually played a similar role in Munich, even if not quite at the same level. His footballing role model was Zidane. “I admired him because he combined physicality and art in football. Zidane could dance and be robust at the same time. That was my dream too,” said Deisler to die ZEIT in 2009. That sounds out of touch, but this almost philosophical approach reverberated a lot with Deisler. “My God, I had utopian dreams. I wanted to be at the centre of the game for Bayern to introduce a new spirit, more joy in the game, more team play and less ego. As a footballer and as a man, I live off of my intuition, my feeling. […] I didn’t have this fixed plan on the pitch, I just saw what my team-mates strengths and weaknesses were, I saw which ball, which pass who needed. That’s my intuition, my creativity, that’s my fantasy. That’s why I played football so well in my better years,” Deisler told his biographer Michael Rosentritt.

***

In autumn 2006, upon his final comeback, perhaps for the first time in his career, this aura of over-the-top expectations didn’t surround him. Many were hoping for a happy ending for him with the World Cup in his own country, which actually seemed within reach for him. A cartilage rupture put an end to that too. By now it’s clear to everybody that Deisler won’t live up to the reputation of talent of the century. Maybe he’ll manage to keep playing at a high level. That’s the yard-stick now.

When Deisler is subbed on in November 2006 at half-time with Bayern 1-0 down to HSV, Bayern’s game changes immediately. Before they had seemed conservative. Passive and harmless. Deisler drifts in from the right and from the first minute he’s the key player in the game. He dribbles, cuts inside, wins the ball, always starting off deep, and is sought out by his team-mates Sagnol, Van Bommel and Schweinsteiger.

In the 56th minute, Deisler is found with a lofted ball in the inside-right position. He takes the ball down on his chest, cuts inside with four players in front of him on the corner of the box. He skins the on-rushing Trochowski with a drop of the shoulder. He looks up. He could play it to Schweinsteiger on the edge of the box, lurking 20 yards out in front of goal ready to pull the trigger from distance. Then he sees Roy Makaay, at Bastian Reinhardt’s back, make a move into the penalty area. Deisler feigns to shoot. Reinhardt seizes this moment to try to play Makaay offside. And then Deisler doesn’t shoot – in the blink of an eye, he instead plays almost a whisper of a pass with his left foot, splitting the Hamburg defence in two, into the space between the goalkeeper and his back-line. All of that happens within half a second. All Makaay has to do is poke the ball past the advancing goalkeeper from five yards. 1-1.

That moment, which I followed from the stands of Hamburg’s Volksparkstadion, was burned into my memory and has stayed with me. It was perfect. The slight delay before Deisler passed completely broke with the flow of the situation. He clearly had to shoot or pass sideways. The whole stadium gradually sat up to take in the situation completely, the noise level rising and rising, because the decisive moment was clearly coming. And Deisler, in half a second, with a slight hesitation, changed everything. As if, for him, the game was just much slower than for all those around him.

Hamburg’s defence had followed Deisler’s every move. First they dropped back, and then they shifted forwards, only to be hit, in precisely that moment, by a perfectly-timed pass into the only place in the box that would enable Makaay to get onto the end of it. It was almost choreographed. It was the best moment, and the best game, that Sebastian Deisler had in a Bayern shirt.

Subsequently, the 26-year-old turned the game on its hand practically single-handedly. He set up Pizarro’s winner too, with good vision from the by-line. Later he would say that he was only able to play freely when he was thrown into a game without thinking. Perhaps this was one of those times. Perhaps it was also the first time in a Bayern shirt that he managed to structure, shape and define a game from the right flank. For those 45 minutes, Deisler was as good as many had always made out. He played as if he was stopping time. In every sense.

***

Two months after the game against HSV. On the 16th of January 2007, Sebastian Deisler retired. Worn down by injuries and by the darkness that he felt on the inside. Exactly ten years ago. If only Deisler had been born into today’s framework of German football. With all of the professional guidance, with a realm of big talents, making sure no one player has to carry all the expectations on their shoulders. On the other hand, it’s pointless to think about it at all, because the reasons for his path to retirement are so complex and difficult to make sense of.

Ten years on, the memory abides of an extraordinary footballer, one who, in his best moments in a Bayern shirt as well, did things that only very few footballers can do. Just like in November 2006. In Hamburg.

Ich war mal zu Besuch auf einer vollkommen abgelegenen Estancia ohne Strom und fließendem Wasser, im Süden von Feuerland. Der Estanciero gab mir ein altes argentinisches Fußballmagazin, und die Titelstory war: “Sebastian Deisler, das letzte große deutsche Talent”. Selbst am anderen Ende der Welt war der Erwartungsdruck riesig. Grüße, Michael

[…] For instance, I remember the case on Sebastian Deisler, a footballer who played for Bayern Munich. Sebastian Deisler was injury-prone in part due to his anxiety. In addition, I also remember the case of Per […]

[…] For instance, I remember the case of Sebastian Deisler, a footballer who played for Bayern Munich. Sebastian Deisler was injury-prone in part due to his anxiety. In addition, I also remember the case of Per […]