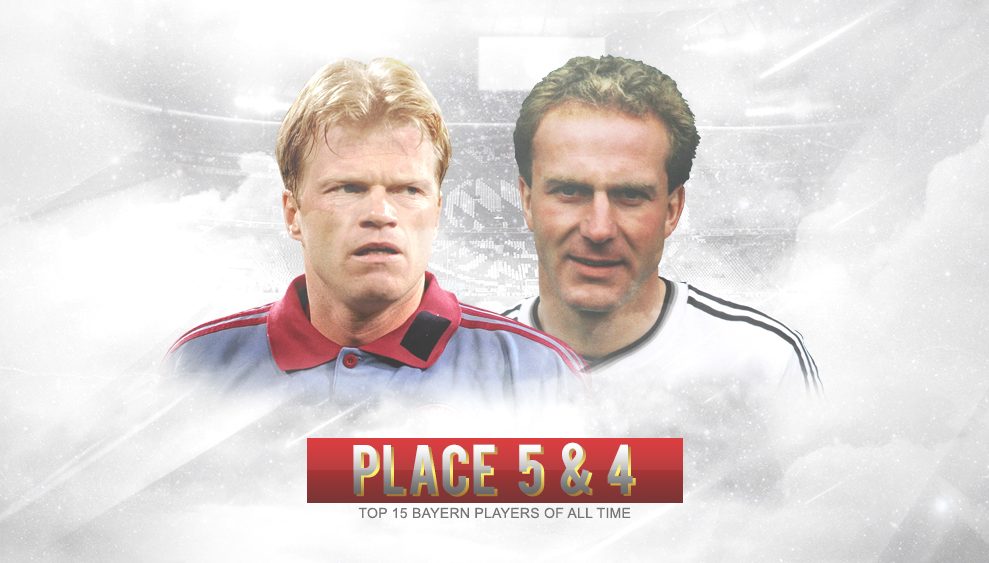

Miasanrot Awards: Place 5 & 4

5th place: Karl-Heinz Rummenigge

by Christian Nandelstädt

Anyone who became a football fan around 1980 couldn’t avoid a blond, red-cheeked, somewhat shy-looking guy with gigantic thighs. Karl-Heinz Rummenigge was the first footballer whom I consciously perceived as a child. The boys in my class were primarily talking about him and his goals. His club, FC Bayern Munich, was only second. So I first became a Rummenigge fan and then a Bayern fan. On the schoolyard we tried to repeat his tricks. A hopeless undertaking. Rummenigge was at the peak of his performance at that time. In 1980 he became not only German champion and top scorer, but in the summer he won the Euros and became European Footballer of the Year. At that time, it was practically synonymous with being voted the best player in the world.

What type of player was Karl-Heinz Rummenigge? Apart from the fact that he is still FC Bayern’s best goalscorer after Gerd Müller, many younger fans don’t know much about him. At least not much from his career as a footballer. The short version: Take a portion of Kylian Mbappé and a portion of Cristiano Ronaldo in equal parts, garnish with a pinch of Wayne Rooney and round off with a touch, but only a touch of Messi.

The long version: Rummenigge combines properties that could have been used to form several top strikers: He was incredibly fast, running the 100 meters in well under 11 seconds. At the same time, he was very strong and dynamic, and was able to assert himself well in duels, which at the time were frequently brutal, but unpunished. Despite his strength, Rummenigge was extremely agile and a great dribbler. A typical Rummenigge goal of the 80s began with winning the ball in midfield, followed by a long run to the penalty area, where two or three opponents were dribbled by like slalom poles or simply overrun and ended with a massive goal at the edge of the penalty area. But that was not a trademark goal. Rummenigge was too versatile for that. He was strong on the header, shot penalty kicks and moved skilfully into free spaces to take passes from Paul Breitner. I don’t have the exact statistics, but Rummenigge was as strong outside the penalty area as inside. There were bicycle kicks and scissor kicks, volleys and toe pokes right in front of the line. Very rarely he also allowed himself an arrogant action. I remember a scene where he walked alone with the ball to the empty goal, stopped the ball on the goal line and then slowly pushed it in.

But also a Karl-Heinz Rummenigge was not as good from the beginning as in the early 80s. His beginnings at FC Bayern were hard. He came as a cheap purchase for about 9,000 euros from Lippstadt into a team full of rich stars who had won everything and could only motivate themselves in European Cup games.

His brother Michael told the Munich newspaper tz 2015 about these difficult beginnings in an interview:

“If you go from Lippstadt to Munich as an 18-year-old in 1974 and are told by six world champions “What are you doing here? – My mother had to come to Munich after three weeks, stayed with Kalle’s then girlfriend and now wife Martina until everything was fine again. Then everything took its course, with Udo Lattek, with Dettmar Cramer, who was a stroke of luck for Kalle, who formed him. And he has learned, absorbed and executed.”

The initially extremely shy player, who turned red when he asked Franz Beckenbauer something and had to be reassured by the coach with a glass of cognac before the kick-off, brought along something decisive in addition to a huge talent: Ambition.

He worked harder under Dettmar Cramer than any other player in the squad, training “12 times a week, while the others had 6-7 units”. Cramer believed in him and used Rummenigge again and again, even though he was considered a Chancentod in his first seasons. As someone who stumbled over the balls in training because of nervousness – “Rumgeflippe”. When the living legend and unattainable role model Gerd Müller left the club in 1979, Rummenigge was able to flourish. With Prussian discipline and the will to become the best, he became the best of his time. Almost always at his side: Paul Breitner, who got on blindly with Rummenigge. Paul, a powerful duelist with an outstanding eye for the free man, found Rummenigge, his executor, everywhere. The press created the term “Breitnigge”. Rightly so. In 1981 both became again German champions with Bayern. While Rummenigge received the goal-getter cannon as he had in 1980, Breitner was named Germany’s footballer of the year. When Rummenigge was voted Europe’s Footballer of the Year in 1980, he again came first – and Breitner second. What a duo, what a great time.

Clubs abroad became attentive to the blonde top striker. First and foremost FC Barcelona. According to legend, Kalle would not have been averse, but his wife allegedly did not want to go to Spain. So Rummenigge remained at Bayern. For the time being. But in 1984 the time had come: Rummenigge moved over the Alps to Milan at the age of 28 as top scorer and DFB Pokal winner. To Inter. For the then record-breaking transfer fee of 5.5 million euros. Only “record-breaking”, because in the same year Diego Maradona changed to SSC Naples for 12 million Euro. The then 11 million marks rehabilitated the indebted FC Bayern – and provided Uli Hoeneß with financial leeway for the first time, which the manager was able to expand exorbitantly in the coming decades. The Rummenigge redemption flowed into debt service (4 million euros) and into the excellent transfers of Lothar Matthäus (1.2 million euros) and Roland Wohlfarth (0.5 million euros).

Rummenigges time at Inter Milan remained titleless. He scored 44 goals in 107 games and was often injured. And yet in an interview he described it as “the best time of my life”. Perhaps because he got to know and love the Italian way of life. Because he understood that in life not only ambition and discipline count, but you should also relax and enjoy.

The Rummenigge transfer was a catastrophe for the Bayern fans. A world ended there. How could a title ever be won again, without Rummenigge’s goal guaranty? Matthäus, Wohlfarth and also Kalle’s brother Michael gave the answer: FC Bayern won the German championship three times between 1985 and 1987.

And Kalle? In 1987, at the age of almost 32, he moved to Switzerland to join Servette Geneva on a free transfer. A deliberately planned end to his career. Two beautiful years, as he told me in an interview for my blog at the end of 2017: “In 1989 I was still playing for Servette in Geneva, which was a small club with considerably fewer spectators than before in Munich or Milan. An interesting experience, because I experienced professional football without pressure for the first time. My Swiss colleagues have always wondered about me: “Say, German, you never get excited. You’re always relaxed.” I replied: “Yes, of course, should I put pressure on myself here now? At the end of the second year of the contract I felt that I lacked the motivation to add another season”.

Here at Lake Geneva, the great career of footballer Karl-Heinz Rummenigge ended in 1989. After 578 games and 293 goals. The trophy cabinet contains one Euros title, two second places at Wold Cups, two European Champions Cups, two German Championships and two Cup victories. In addition various personal awards.

His second career as an executive can still be followed today. I have reported about these decades in detail in my blog. But I will never forget him as the fantastic soccer player who made me a Bayern fan.

4th place: Oliver Kahn

by Redrobbery

„Weiter, immer weiter!“ – rarely has a professional soccer player succeeded so well in describing his own character. Giving up was never an option for Oliver Kahn. Self-doubt was for him the first step to defeat. This is not the only reason why he is regarded in many places as the best goalkeeper in the history of the club – despite his well-known competitors.

Compared to other club legends, Oliver Kahn came to FC Bayern late. The 25-year-old was hired by Karlsruher SC for just under 5 million marks. Kahn was already convincing both nationally and internationally in his hometown – after all, he was part of the legendary UEFA Cup campaign in his last season, in which the KSC celebrated a 7-0 victory over Valencia and only failed in the semi-final because of the away goals rules. The ambitious goalkeeper only conceded seven goals in ten games, keeping a clean sheets five times.

After watching the 1994 World Cup from the benches, Kahn took over the role of Raimond Aumann’s regular goalkeeper at FC Bayern, who moved to Turkey. The first year was not an easy one. In the Bundesliga, they only finished sixth. Oliver Kahn himself could only play 23 league games – this should remain his lowest number.

In the following year he won the first title of his career. Completely atypical, like many things with Kahn: it was an international competition. FC Bayern won the “Losers Cup” ( officially UEFA Cup). Only weeks later, Kahn (still in the substitute role) was even allowed to raise the Euros trophy for the national team in England.

Now a hunger for the title developed that could never be satisfied. Kahn’s yield is remarkable: eight championships, six cup victories, UEFA Cup, Champions League, European champion.

The only flaw in the trophy cabinet is a tragic one: Oliver Kahn never became World Cup winner. Three of his four World Cup appearances were only in a passive role. Only once – remarkable in this career – did he enter the stage as a regular goalkeeper. In Japan and South Korea, Kahn delivered probably the most dominant goalkeeper performance in the long history of the World Cup. Five of the seven games he played showed him to be in world-class form – he was not challenged against Saudi Arabia, in the final he became a tragic figure. If he had led the dust-dry national team to the title against Brazil, his name would have appeared in FIFA history books alongside Maradona and Pelé.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

Not much needs to be said about Oliver Kahn’s performance at FC Bayern. Everyone who was able to experience this time remembers it with pleasure. At a time when the club was mostly defensive and waiting, he managed to save the results over time almost weekly.

There are numerous stories and anecdotes that come to mind for every football fan about Oliver Kahn. From Bayern’s point of view, only three of them should be mentioned here that symbolize the Kahn character.

The notorious golf ball throw in Freiburg is one of them. In April 2000, a heated game developed in the otherwise tranquil city of Freiburg, which reached its low point in the aforementioned act. However, Kahn’s reaction to this incident was remarkable and symbolic. No theatricality, no creeping departure – for Kahn the only option was victory. He stood back in the goal, strongly marked, with the angry pack, including the perpetrators, behind him again. To give in would be to give up and Kahn does not know giving up.

The greatest moment of his career was probably one week in May 2001: last minute champion and immediately afterwards Champion League winner. Unforgettable are the saves in the penalty shootout against (once again) Valencia, but much more significant was a small action in Hamburg a week before. In the excitement of the indirect free kick, Kahn marched into the opponent’s penalty area to use his physical presence to create unrest and gaps in the opponent’s side. Nobody knows whether his action made any difference. But it is typical for Kahn that he tried everything in his power to influence his team’s chances of success.

The third memory is a supposedly inconspicuous one. In the autumn of his career, Kahn and the FCB were allowed to go to St. Pauli in the DFB Pokal. It was a tough, unpleasant game in a difficult phase – only days before his degradation in the national team was announced. Despite the lead, the team didn’t really get their bearings, it smelled like sensation (among many other things at the Millerntor). Captain Kahn had a very good feeling for such moments. With the playing time running down, he became more and more aggressive and challenged opponents. But for him this was no loss of control. Such actions were specifically used to steer opponents as well as fellow players into corresponding emotional channels and to change the course of the game in favour of his team.

Calculated impulsively, dominant holistically and focused 100% on success – that was Kahn.

Between 1998 and 2003, Kahn reliably delivered world-class performance. It was probably one of the most dominant goalkeeper phases in football history. Performances such as in the Bernabeu in the legendary 2001 season, when Kahn brought the Madrilenian star ensemble to despair for over 90 minutes, were more a rule than an exception. Within the club, the Neuer era from 2012 to 2017 reached similar spheres, but was accompanied by a more dominant team structure and is therefore already quantitatively inferior.

Only a few players have the necessary charisma to influence an entire team, let alone mentally manipulate their opponents. Oliver Kahn could do this. The fear of failure was already visible in many strikers before they even took their shot towards Kahn. Kahn was so self-confident and dominant that he weakened his opponents as he strengthened himself and his teammates.

Oliver Kahn was one of the greats in the goalkeeper area. In the psychological area there was hardly a better one. Kahn had only one weakness: Sammy Kuffour.