Carlo Ancelotti: What can FC Bayern expect?

In Carlo Ancelotti, his successor has already been confirmed. We will introduce the Italian in our portrait, work our way through his past, and have a sneak peek at the future.

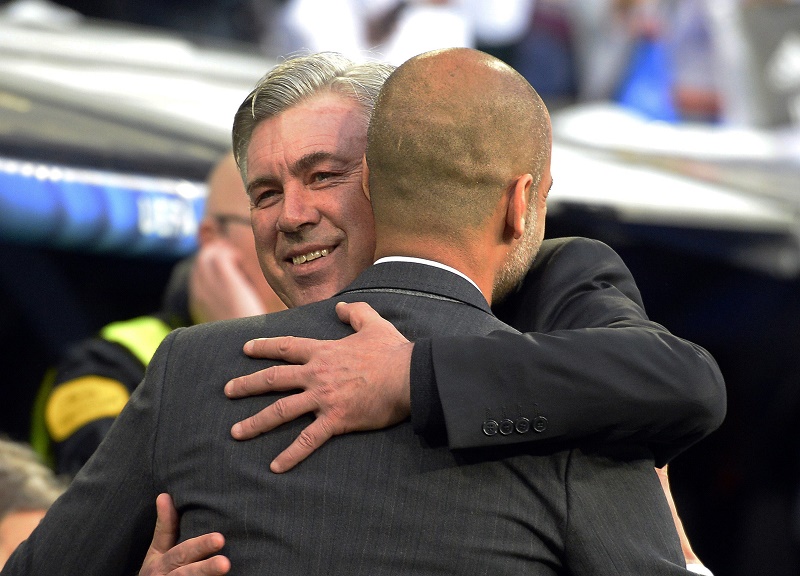

Ancelotti is a very calm person, without the typical Guardiola emotional outbursts on the side-line; instead, he is said to be fairly calm and pragmatic. While Guardiola often seemed offended and failed to hit the right tone when dealing with the media, the future Bayern coach has rarely – if ever – had moments like that; he is a professional in working with the media. “Carletto”, as he’s sometimes called, doesn’t like being the centre of attention and doesn’t feel the need to put himself into the spotlight. Many of these attributes can be traced back to his career as an active player.

AC Milan’s strategist

Ancelotti was part of a team which, to this day, is heralded as one of the best and most successful of all times: AC Milan, the last club to defend the then European Cup, winning it in 1989 and 1990 under Arrigo Sacchi. Carlo Ancelotti had a very strategic position as a holding midfielder, and even though he played with some all-time greats like Gullit, van Basten, Maldini, or Rijkaard, Ancelotti was not forgotten. On the contrary, he played a pivotal part. Looking back at the team’s structure, there are several obvious parallels to the teams Ancelotti would go on to manage in his career as a coach.

While playing at Milan, Ancelotti was the perfect partner for his counterpart in defensive midfield, Frank Rijkaard. In a flat 4-4-2, they were the link between offense and defence: while Rijkaard was a very defensive holding midfield, though not without the necessary technical skills, Ancelotti was the strategist in Arrigo Sacchi’s formation. Typically, the Italian was placed quite deeply, where he distributed the balls and looked good even under pressure, or in tight spaces, and he was also involved in offensive plays. Sacchi was one of the most important figures in football’s tactical development, and to this day he, like no other, stands for the reduction of space for opposing teams. By constantly, compactly moving the team, the opponent was forced into making mistakes; making space tight around those players close to the ball. Before Sacchi, it was the common thing to focus on each player’s direct opponent; he, however, favoured compactness and his team focused on the ball rather than individual players. He and his team weren’t just ahead of the curve in terms of tactics, they also became role models for the way football was going to be played in the future, and on top of that, one of the most successful teams of all times. Ancelotti himself would remember and apply plenty of ideas from that time later on.

Starting strong, and an era at AC Milan

Ancelotti’s first position as coach was with the Italian national team, where he worked as assistant under his former coach Arrigo Sacchi between 1992 and 1995. At the 1994 World Cup, they reached the final together, but lost to Brazil on penalties. “Carletto” signed his first contract as head coach with AC Reggiana in Serie B in 1995 and led them into Serie A in his first season. After that, he moved on to AC Parma, where he continued his success and managed a surprising second place in the league in 1996/97. His time at Juventus Turin, where he took over from Marcello Lippi in February 1999, wasn’t as successful: although he managed to win the UEFA Intertoto Cup (UI Cup), he failed to win the league title twice and, after failing in the Champions League group stage in 2000/01 (against Hamburg, Panathinaikos, and La Coruña), he was replaced by his predecessor Marcello Lippi.

The biggest and most successful era of Carlo Ancelotti, however, was still to come: on November 7th in 2001, he replaced Fatih Terim as AC Milan’s head coach, and went on to build an era. He had never been known for complete team overhauls at his previous jobs, and he followed this line at Milan as well, trusting the team he had been handed. During the summer transfer periods, the purchases were all aimed at improving single positions, with good examples for this being Kaká, Ronaldo, and Cafu. In the beginning, though, things weren’t going too well for Ancelotti. He continued with Milan’s tactical formation at the time and played a tight 4-4-2 with a midfield diamond, with Pirlo who, at the time, was still positioning himself as a number 10 behind the two strikers. Dortmund fans might still remember the game on 4 April, 2002, when BVB beat Ancelotti’s Milan 4-0 at home, in the low point of a rather average season. Longer spells of possession and successful passing were non-existent, instead they trusted long balls. In the league, he only reached the fourth place in his first season. Despite this, Ancelotti went on to reach the Champions League final three times during his tenure at Milan.

„Carletto“ had to change some things in the 2002/03 season to keep his job. With the transfer of Clarence Seedorf he gained a player who could give his team more offensive momentum. He took over the position on the left in the midfield diamond next to Andrea Pirlo, whom Ancelotti moved deeper to act more as a strategist. These changes led to a more offensive style of play and, with that, much better solutions in midfield and longer periods of ball possession. The team became less dependent of its individual class and gained more control in midfield, while at the same time not forgetting their defence entirely. In the league, they couldn’t get further than third place, but they won both the Champions League and the Coppa Italia. In the Champions League semi-final, they beat Inter Milan and went on to beat Juventus Turin on penalties in the final. It was a very balanced final, which saw Ancelotti give up his diamond midfield in favour of a flat 4-4-2 with Pirlo and Gattuso in defensive midfield. It wasn’t a very pretty game, but a very contested one, with a lucky finish for AC Milan; it also made Ancelotti one of only 6 people who won the Champions League as a player and a coach, like Miguel Munoz, Giovanni Trapattoni, Johan Cruyff, Frank Rijkaard, and Pep Guardiola.

In 2003/04, Kaká joined the Champions League winner. The young Brazilian was supposed to turn into a regular behind Rui Costa, which he achieved much faster than anticipated, leading to his big breakthrough. Ancelotti and his team won not only the European Super Cup that season, but also the Scudetto, the Italian league title, for the first time. There were hardly any new tactical developments during that time, but then again, there was no need for them: Ancelotti’s system worked, and the team was successful. Even then it was becoming clear that he wasn’t going to make any major tactical changes during the course of a season. He was always focused on combining the individual class of his players in a way that put a successful team on the pitch. The very compact, but by all means still offensive AC Milan hardly changed during Ancelotti’s era and when it did, it was only slightly. Pirlo and Kaká were the major players in the centre, with the Italian starting off behind the strikers and later moving to the more strategic position in defensive midfield. At first, Rui Costa moved into the 10 position after Pirlo, later Kaká would have many successful years there. Inzaghi, Gattuso, and Maldini were other big names in the system, and it was this flexibility in midfield, brought on by so many different types of players, that decided many games in Ancelotti’s favour.

(Photo: Paco Serinelli / AFP / Getty Images)

He was part of probably the most spectacular Champions League final in history: In 2005, Liverpool and AC Milan were facing off in Istanbul, and the Italians’ first half has to be one of the best football that the 2000-10 decade had to offer. Liverpool was completely overwhelmed and down 3-0 at half-time. Putting two players into both defensive and offensive midfield who could control and steer a game put the English into a difficult situation: they could take out either Kaká or Pirlo, but hardly ever did they manage to eliminate both, due to the special constellation and the players’ individual class. When Pirlo was under attack, other team-members in the half spaces could channel the game towards Kaká, who in turn could use the newly-created space behind the opponent when moving forward. If Liverpool sat back deeper, Pirlo was able to use the empty space around him and become dangerous. The two players were the pivotal element in Ancelotti’s team, and it took Rafa Benítez until half-time to find a solution against them: after the break, he switched to a back three, which created bigger presence in midfield, consequently bringing his team back into the game. Ancelotti didn’t have much to counter this with and waited too long to adjust his own system; by the time he switched to a back three as well, the game was already at 3-3. The team looked shocked and had completely lost their grip on the game, going on to lose it all on penalties. The strongest 45 minutes in Ancelotti’s era ended with absolute horror, and the loss lay heavily on the Italian coach’s shoulders after reacting too late.

After 2005/06 brought no titles at all, both teams faced each other again in the Champions League final in 2007. Ancelotti had gone through against Bayern in the quarter-final with a 2-0 in the second leg, after drawing 2-2 in Milan, followed by a 5-3 on aggregate against Manchester United in the semi-final. And then, the final: revenge against Liverpool. Ancelotti gave up his usual midfield diamond and positioned Kaká even more offensively, to give the Brazilian even more freedom. Pirlo and Ambrosini were the holding midfielders, while Seedorf and Gattuso occupied the wings and half spaces, aiming at countering Liverpool’s massive central presence with Alonso, Gerrard, and Mascherano.

However, the English team seemed to cope well with these tactical changes, and were threatening to decide this game in their favour, too. Liverpool dominated from the get-go and left no doubts about who was the better team, until a lucky goal by Inzaghi just before the half-time whistle changed the course of the game. After going up 1-0, Ancelotti changed his game plan completely and discarded his offensive positioning, choosing to defend the result and focus on counterattacks instead. Liverpool couldn’t create any more good chances, and Inzaghi even scored again to make it 2-0. Kuyt managed to get one back just before the end of the game, but in the end, Ancelotti could celebrate his second triumph as a coach in the Champions League after 2003.

Ever since that success, Ancelotti had ascended to be one of the most successful coaches of our time. He went on to add the UEFA Super Cup and the FIFA Club World Cup to his collection before ending his era at AC Milan, which will remain unforgettable. While he didn’t revolutionise football there, he always managed to get the maximum out of his – fairly old – team, and often made the right decision at the right time. His biggest strength was putting the right players into the right positions, giving them the opportunity to make the best of their individual strengths. The young Kaká had his best time under Ancelotti, and he had significant influence on Pirlo’s development; however, he kept using the same players over and over, and through the years missed the chance to rejuvenate the team.

His era in Milan was followed by several successful years in London and Paris. He would have to move to Real Madrid, however, before he could win the Champions League again.

To Paris via London

Despite the exhausting time at AC Milan, he took over FC Chelsea directly afterwards in 2009. In London, “Carletto” and his team beat the goal-scoring record in his first season, won the league title and the FA Cup, but still left the Blues in the following season. In London, like in Milan, he made only few changes to the existing team and mostly worked with what he already had on hand. Centre-forward Drogba was the team’s outstanding player; in a 4-5-1 the Ivorian was the central man in offense, supported by wingers who moved forward proactively to turn the formation into a 4-3-3 when necessary. The main focus of the game plan was to stay compact in midfield and make the most of Drogba; this was helped further by Frank Lampard, whose clever movements out of defensive midfield into the offensive centre created superior numbers for Chelsea and supported his striker perfectly. Like in Milan, Ancelotti rarely ever tried to adapt to an opponent while at Chelsea and instead chose to focus on their own strength.

Ancelotti returned to 4-4-2 when he moved on to his next club, taking over French club Paris Saint-Germain in winter 2011/12. In preparing for the 2012/13 season, PSG bought players like Zlatan Ibrahimović and Thiago Silva. In front of the back four, he placed Verratti, a deep-sitting strategist who distributed balls, and Matuidi, an offensive-minded box-to-box player, with Beckham and Motta two other big names for this position in Ancelotti’s team. Jallet delivered a very offensive interpretation of his right-back position, ensuring occasional advances. Matuidi secured the area behind the Frenchman or pushed up be the team’s spearhead himself, with both communicating well with each other. Maxwell, who usually played left-back, was generally more defensive and sat deeper than his pendant on the right; this asymmetric structure made it difficult for the opponents to get a good grip on the game, especially in Ligue 1. Up front, there were four players with immense individual quality. Pastore and Lucas occupied the half spaces behind Ibrahimović and Lavezzi, with all four equipped with certain freedoms. Despite this well-functioning basic formation, they only achieved the league title. In the Champions League, they went out in the quarter-final against Barcelona despite not actually losing; a 2-2 at home and 1-1 in Barcelona meant the end of their campaign. Ancelotti himself ended his spell in Paris in the summer, wanting to take on a new challenge at Real Madrid.

The difficult life of a Real Madrid coach

There, he took over from José Mourinho. Out of all of Ancelotti’s teams, this Madrid team was probably closest to Sacchi’s Milan of 1990. Benzema and Ronaldo played as attackers, complementing each other well and occupying spaces ideally. Their runs, too, were well aligned. There was a slight asymmetry on the wings, with Di Maria on the left and Bale on the right wing. While Bale kept pushing forward and tried to give their game more width, Di Maria positioned himself closer to the half space or even in the centre, to support the midfield. In doing so, the Argentine took on something like a playmaking role. This move inwards led to overloading on the right side and an asymmetric 4-3-3. Di Maria kept finding good balance for his position and made it harder for the opponents to keep up their compactness. Alonso and Modrić played as holding midfielders, with the Croatian the more defensive half of the duo and Alonso a technically strong ball-winner, who dictated speed of play – especially when in possession – and took on strategic tasks. This splitting of roles was very reminiscent of Rijkaard and Ancelotti during their time at Milan.

In addition, the two fullbacks were very high up the field. This hybrid between 4-4-2, 4-2-2-2, and 4-3-3 should earn Ancelotti the Copa del Rey and his third Champions League title as a coach. In the 2014 final they luckily, but deservedly, beat Atlético in the Madrid derby. They needed a Ramos header in injury time to even make it into extra time, but then dominated exhausted Atlético and secured the cup with a 4-1 win. “Carletto” brought Madrid “La Decima” (the tenth Champions League title) and was the first Real coach since 2002 to win an international title. Some Bayern fans might still remember the semi-final.

Based on these two games against Bayern, some reduce Ancelotti to be good for nothing but counterattacks, but this is far from true. He only used this highly effective tactic against the possession-loving teams from Barcelona and Munich, but against more defensively focused opponents, his teams generally show very good solutions when in possession. Real Madrid was very flexible under Ancelotti and never used one style of play exclusively; they were strong both with and without the ball.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

After Bob Paisley, Carlo Ancelotti is only the second coach who won the Champions League three times. In addition to the two titles in his first year at Real, he won the UEFA Super Cup and the Club World Cup the following season. Despite all this, he was let go at the end of the 2014/15 season, after coming second in the league by only two points, exiting the Copa del Rey in the round of 16 against Atlético, and not being good enough against Juventus in the Champions League semi-final. It wasn’t enough for the club, and Ancelotti found out what it really meant to be Real’s manager when after an extremely successful year with “La Decima”, he couldn’t keep up the momentum. The team’s superstars still speak highly of the Italian to this day, and Ronaldo and Kroos have mentioned repeatedly that they would have liked to continue working with him.

Ancelotti couldn’t have taken over in Munich at a more difficult time. What can FC Bayern expect, and which tasks are waiting for the Italian?

Bayern will get a coach who is very flexible. Ancelotti doesn’t force his ideas on anyone, and he’s not one for putting himself on centre stage. But of course he is a coach with ideas, demands, and a certain consistency. The Italian isn’t one of the very tactical coaches with plenty of changes and adjustments. Guardiola’s biggest strength is his ability to read a game and to turn around the course of a game with his coaching. Most of all, though, he is a coach whose basic formation depends very much on the opponent, after analysing the other team for days. Ancelotti, on the other hand, prefers to focus on his own team’s strength, and tries to find a formation in which every player can reach their maximum performance, all the while keeping team dynamics alive. He has played counter attacks in his career, but he has also had good, dominant games with great ball circulation.

He will be able to profit from the impressive variability that Guardiola has taught his team; thanks to the Catalan, the players have a good understanding both of the different phases of the game and the occupation of spaces. The current positional play will help Ancelotti a lot and make his life easier. Language shouldn’t be an issue; Bayern’s team is fairly international to start with, and Ancelotti speaks four languages. During an interview in February, he joked, “If Giovanni Trapattoni could learn it, so can I.” After a mentally challenging coach like Pep Guardiola, Ancelotti might be the perfect man for the German record champion; the pragmatist can handle big names and is well-known for giving his teams strong form in the final, decisive games of a season.

However, “Carletto” has never been a big fan of rotation, and he might have to adapt to FC Bayern in this area. Munich’s squad is very strong, and easily 18 top-rate players deep; these should be rotated frequently to avoid conflict. On top of this, his role in the development of young players will be exciting: Kaká had a great time under Ancelotti while he was still young, but there weren’t a lot of young talents that he coached to great players during his career. Kimmich and Coman have both proven their class already, and Sanches will be another young player who wants to become a regular in Munich; it will be interesting to watch how the Italian will deal with them. It is fair to say that Guardiola leaves the club in the middle of a big change, and whether this will lead to a dip in performance next year or whether the new coach will be able to continue the current winning streak will be one of the big questions to answer.

(Photo: Gerard Julien / AFP / Getty Images)

Looking at tactics, his hybrid between 4-4-2 and 4-3-3 could be an option, but it’s also possible that he takes a page out of Guardiola’s book and adds a back three to his repertoire. Due to his variability in the past, it’s impossible to say what Ancelotti is planning, but a 4-4-2 and, with it, a return to Bundesliga tactics mainstream is the most likely option, as he will hardly want to break up the goal-scoring duo of Lewandowski and Müller. On the wings, Robben could become a regular starter again once he’s back to his old form, and Costa, Ribéry, and Coman will compete for the other position. That would leave two positions in central midfield, with new transfer Sanches, Arturo Vidal, Xabi Alonso, and Thiago as favourites for the roles. There are transfer rumours around the latter, but it’s difficult to say how probable a transfer really is, especially considering he renewed his contract at the beginning of the season. Joshua Kimmich and Javi Martínez are both originally midfielders as well, but Kimmich could also play as a right back whenever Lahm is given a break. For Martínez, it’s not yet decided where Ancelotti sees him; the Spaniard too is very flexible and can play both as a centre back or a holding midfielder. Rode will likely have to find a new club. The future of Mario Götze is still unclear. Rafinha is another player who might leave Bayern. Mats Hummels’ signing also makes life more difficult for Medhi Benatia, and although his agent has hinted that he will stay, a transfer isn’t completely out of the picture yet. There will likely be additions for the positions of right back and striker.

Bayern is heading into a new phase that will be interesting at the least, with Ancelotti arriving in the middle of a team upheaval, leaving him with anything but an easy task. In the second half of the 2015/16 season, Guardiola became as pragmatic as probably never before, with hardly any big surprises. It is likely that this is the FC Bayern we can get used to now, since the new coach will probably act much more predictable and run a lot fewer experiments. Maybe opponents will have an easier time preparing for the record champion in the future, but that doesn’t take anything away from the players’ individual class.

Ancelotti’s main task will be to successfully finalise the change in the team’s structure and to slowly reduce the reliance on older players. During his time, he will have to find solutions to replace Ribéry, Robben, and Lahm, while at the same time developing young players like Coman, Kimmich, and Sanches. After four league titles in a row it will only get more difficult for Bayern. Everybody’s waiting for a little break in their form, and this transition seems like the ideal time for it. Preventing this from happening and being successful immediately will be another task for the Italian. On top of this, there are smaller areas that need working on, like the focus on the wings that was an important means for Bayern’s success. Reducing this and finding new, better solutions for openings through the centre or the half spaces would be desirable. It’s not an easy task waiting for Ancelotti in Munich, but he has the skills to continue the previous, successful years.