The breakthrough of Philipp Lahm

On February 18th 2004, when Philipp Lahm made his debut for the German national team against Croatia, he did this as a left-back, indeed a position that he had only occupied for the first time five months previously.

This debut, in which he, naturally, filled the role to the highest level, at the same time marked the beginning of a dominance that was completely unforeseen, paralleled at best by Franz Beckenbauer in the libero position, in German football, which hasn’t exactly lacked outstanding players throughout its history. Due to the erstwhile gulf in quality between Lahm and the competing players, until the end of his career his dominance remained uncontested to such an extent that his biggest competition as a left-back was himself in his role as a right-back and vice versa. And it’s not too unrealistic to add that his retirement from football, first internationally and now domestically, might not automatically equate to the end of that dominance: after all, who would contest that Philipp Lahm, at least through the 2018 World Cup, would have remained Germany’s first choice both at left back and right back?

We’ve now, in principle, covered almost everything regarding Lahm’s high-profile position in football history, and for some it may seem redundant, what with the current songs of praise that are being granted to him upon his retirement, to write a further evaluation of this outstanding footballer. And yet I am convinced that Philipp Lahm, in spite of everything, has still not been appreciated enough, and there is a real fear that in the future this situation won’t change for the better. For example, Philipp Lahm has not once been selected by journalists as Germany’s Footballer of the Year (his best result was 2nd place in his first season in 2004, behind Ailton) and so doesn’t just stand in the shadows of greats like Beckenbauer (4x) and Ballack (3x), but also behind players like Marco Reus or Grafite, who both became Football of the Year during Lahm’s career. Of course, attacking players have an advantage in these awards, but at the same time the defender Berti Vogts won the award twice, and from Karl-Heinz Förster to Jerome Boateng there have always been defenders who have been recognized.

Motivated by the worry that in 20-30 years Philipp Lahm will only be remembered in YouTube clips as a goal-scorer against Costa Rica or as a one-man wall up against a Cristiano Ronaldo free-kick, and in a historically revisionist manner given less importance than dribble kings or goal-scoring wide forwards, this article shall contextualize and illustrate the first half of Philipp Lahm’s career. The fact that an analysis of Lahm will simultaneously offer an appraisal of him is inevitable.

The situation of Philipp Lahm having been Germany’s undisputed best full-back over the last decade and a half is, of course, not solely explained by his brilliance, but is the result of a combination of diverse factors. For one, German football experienced its most serious crisis to date at the turn of the millennium.

The selection of players of international quality was so negligible that it wasn’t only the outstanding talents like Philipp Lahm that were fast-tracked into the national team, as would probably have been the case in other countries, or in Germany in prior years; clearly less talented players like Lukas Podolski and Per Mertesacker managed to break through early on and were able to hold down a place in the team from a young age, setting the foundations for long international careers.

Two areas of German football were of particular concern: defending in the back-four and creativity, which was above all seen in a complete inability to win offensive battles – so-called one-on-one situations – or even to get into those positions in the first place. In both areas, Philipp Lahm at the beginning of his career represented a quantum leap forward in comparison to the established players at the time, even though they weren’t necessarily among his genuine strengths, as it transpired. But one thing at a time.

Lahm as an academy player 2001-2003

Since he was 11 years old, Lahm played for FC Bayern, and so profited from, contrary to nationwide reputation, a good and relatively advanced youth programme. In 1995 the youth system was restructured and in the form of the “Junior Team” a unified playing system for all academy teams was also established. This led to the back-four taking hold itself bit by bit, and indeed well before it began to take hold in the senior side. Indeed, Lahm played in midfield in the youth sides, preferentially as a ‘number eight’, or rather “a defensive midfielder with a little more licence to go forward” (as he put it himself), and so didn’t have any basic education as a member of a back line; it is, however, not insignificant to have become familiar with this system already as a child/teenager, even without having grown up in it.

It should not be forgotten that switching to a back-four in Germany required doing so with players who had grown up with man-marking and liberos. This situation could not be overlooked either. The 2004 European Championship was the first tournament in which the German national team consistently operated with a back-four; however, they did so with centre-backs like Nowotny and Wörns, who in their basic tactical disposition were worlds apart from modern centre-backs, and constantly attempted to rely on the familiar man-marking/libero model in pressure situations. So it wasn’t for nothing that Jürgen Klinsmann as the coach decided to turn to a new generation, above all in defence. Players who had internalised the system in their youth (Mertesacker under Slomka/Rangnik at Hannover 96; Huth at Chelsea). Right at the start of his career, Philipp Lahm had to play with both types of central defenders. Due to his very own game intelligence, he managed, apparently effortlessly, to adapt as and when necessary to these fundamentally different types of team-mates in the back line.

It is certainly unlikely that Lahm’s versatility could be traced entirely back to it, but the method of FC Bayern’s head of academy at the time, Udo Bassemir, not to limit a player too early to a single position, and instead to educate them in at least two positions, certainly did no harm to his development. Back in the U19 Euros in 2002, where he reached the final with Germany (0-1 against Spain, Fernando Torres scoring the goal) he operated as a midfielder. It was only under Hermann Gerland in the Bayern reserves that he was consistently played as a right-back. In this position, he managed for the first time to decisively rise above his peers.

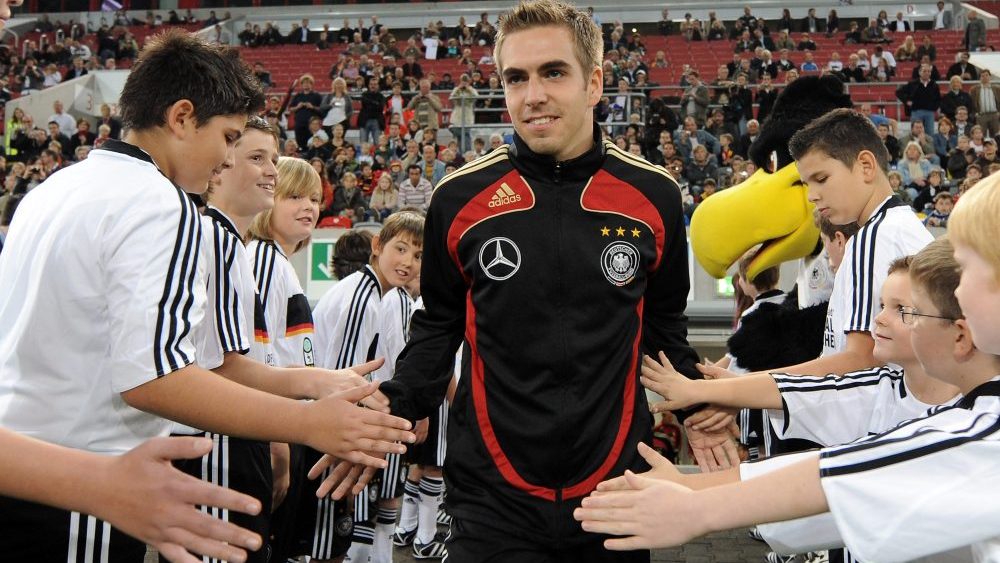

(Photo: Christof Koepsel/Bongarts/Getty Images)

Of course he was also already an integral component of Bayern’s teams that were champions of Germany’s premier youth division in 2001 and 2002. He was a youth international and seen as exceedingly talented; however, as a midfielder he still remained in the shadows of other players, which went for domestic level as well as international level. As such, Lahm was only brought on as a substitute in the U19 Euros final for example (alongside David Odonkor), and at club level players like Trochowski, Schweinsteiger or Feulner were instead trusted to break through into the senior side.

As a right-back, however, Lahm impressed in the reserves with the very same consistency that still marks him out today. And yet he wasn’t able to make a lasting case for himself as far as the senior side went. On the one hand, his position was already blocked for the foreseeable future by Willy Sagnol, still very young at the time, and on the other hand Lahm, with his size and stature, didn’t quite give the impression that he would be able to compete physically in the business of the Bundesliga. Hermann Gerland is the one to thank for saving Lahm from a third year wasted in the reserves, freeing him from that potential dead end. Gerland recommended him to Felix Magath, who at the time was causing havoc with so-called “wild youngsters” like Kuranyi, Hleb etc, as a back-up for Andreas Hinkel. And so Lahm was loaned to VfB Stuttgart for two years.

Loan to Stuttgart 2003-2005

From the sixth matchday onwards, when he made his debut in the starting line-up against Borussia Dortmund, Philipp Lahm was a key player and it was unthinkable to remove him from the team. This was a scenario that would repeat itself just 5 months later with the national team. Having ousted Stuttgart’s left-back at the time, Heiko Gerber, in principle he only had to fill a temporary gap in the national team, since this position had previously been occupied by players like Tobias Rau or Christian Rahn, with performances less than pleasing. With the style of play he had shown in the lower divisions, he was able to effortlessly deliver the same quality in the Bundesliga as in the national side. In such a way that one wondered why this idea hadn’t occurred long before. To those who today struggle to imagine Philipp Lahm being just a back-up for Heiko Gerber, listen up: at the end of 2003, that was still thinkable.

The reason for his seamless transition from the lower divisions to the Bundesliga was that the qualities that Lahm’s performances in the academy and the reserves, showing him to be a class above the rest, were, in contrast to many of his peers, not based on attributes that would level out all too quickly when making the leap to the professional level: his game wasn’t about permanently having to outpace opponents on the wing; nor did he win particularly many tackles due to an outstanding physique. In excellent ball control, passing accuracy, quick perception and high game intelligence, he had at his disposal qualities which he – in spite of the clearly higher speed of football – was able to rely on at professional level just as he always had before. And so as a reserve player he may not have seemed to the observer like a player of immense talent clearly below his level in the lower leagues. Precisely because his superiority, due to his playing style, was not eye-catching or immediately visible for all to see, like for example when the 17-year-old Ronaldo was playing in the Eredivisie. But once he got there, Philipp Lahm made the jump to professional football with consummate ease, because he hardly had to change his style of play, and simply had to put into practice what had set him apart from the rest – in an unfamiliar position, let it be remembered. Because until his professional debut on the left side, he had previously never played there before. Neither in the academy nor as a reserve in the lower leagues. In just his third appearance at all as a left-back on the 1/1/2003 in the Champions League, in a 2-1 victory over Manchester United, he contested a direct battle against Cristiano Ronaldo, which he managed with courage.

(Photo: Friedemann Vogel / Bongarts / Getty Images)

When in interviews it was put to him that, as a right-footer, he was actually playing on the wrong side, he played down the significance of the situation, because “left is just like right, only on the other side”. He would go on to amend this when he looked to switch to right-back at FC Bayern, namely by arguing that as a right-footer on the left he was easier to beat, since defending the line was harder with his right foot.

But for now he was just over the moon to have made the leap to professional level, and a long way away from making such claims. To trust himself and simply get on with it, instead of pondering his own suitability, sums up Lahm’s first year as a professional. Due to his personality, in principle he’s not the kind of person to be aggressively making demands, but when opportunities present themselves, he doesn’t want to have to be reproached that he didn’t use them. That goes for the opportunity to move up to the first team in an unfamiliar position, just like years later for the chance to make a claim for the captain’s armband of the national team.

In general, the start of Lahm’s path as a professional was based on having relatively few instructions and simply being left alone to deal with it. Lahm was thrown into the deep end, with the time for reflection and tactical considerations yet to come. With Felix Magath he experienced little more than a general description of his tasks, which mostly consisted of “tight on this side” and, if possible, “mount pressure on the flanks”. This, Lahm describes in his book, was hardly different to Rudi Völler in the national team, rather somewhat less harmful tactically. It’s noticeable that he was used to more tactically-descriptive training from his education at Bayern Munich. It’s hardly imaginable what would have been possible for a player like Lahm, had he had a coach in his early professional years who could demonstrate clearly and precisely what the concrete requirements of him on the pitch were. Lahm was always a player willing to learn, but in his early years he lacked the relevant input to allow him to ‘acquire’ his unfamiliar position from scratch.

The second part will take a closer look at Philipp Lahm’s development in his Bayern time between 2005 and 2009.

Return to Munich 2005-2007

‘Acquire’ is an important word here since Philipp Lahm was among the offshoots of a generation of players who were not able to intuitively switch to a back-four because back-fours and zonal marking weren’t bread and butter from a young age. Lahm had to adapt intellectually to the back-four, and that was clearly visible. During his early years at Bayern you could almost see how desperate he was defensively to deliberately implement the behaviour in a back-four that was found in the textbooks. All too deliberately. Because his moving inside and narrowing of the backline when opponents attacked through the centre, and also his overlapping on the flanks during attacks was, in the years before Van Gaal, still very schematic and not particularly fluid. He put together the stages of action in the right order, but at times in the way that a driving student, before turning, sees to the brakes, shoulder check, clutch, gear and indicators one after the other. All too mechanically and hurriedly did Lahm shuffle inside upon central attacks so as to offer no gaps there. By doing so he opened up huge spaces for the opposition out wide, which they could push into almost unopposed, thus being presented with a clear potential move.

Of course, Lahm wasn’t actually the one at fault here, but rather a lack of shuffling across on the part of the remaining members of the back line, who were often too lethargic for that; but the lack of coordination in the back four shows how Lahm was careful in those years to pay attention to himself and his own performance first and foremost. Indeed, during those years he was, alongside Ballack, the only player of genuine top international quality, but his status still far from allowed him to assume control of the defence.

Other than himself, however, his defensive behaviour was of no interest to anybody. A full-back in a back four at that time in Germany was predominantly judged, like a wing-back in a 5-3-2, on what he did in attack, particularly at a club like Bayern Munich, where defenders have been more occupied with attack than defence since the dawn of time. Philipp Lahm was assessed by the public as first and foremost a creative player, and thus valued for his strengths in one-on-one situations, and in the years before Ribéry, Lahm actually functioned as a disguised playmaker. With Scholl mostly just coming off the bench, Zé Roberto as an exclusively left-footed player being too easy to isolate on the flank, and Deisler never being a consistent great, it fell to Lahm to open up the opposing marking structures and thus generate ideas for a move to unlock the defence.

(Photo: Sandra Behne /Bongarts / Getty Images)

Over and over again was the ball shifted across to the left towards Lahm by centre-backs or midfielders with the demand “Come up with something!”. Not only was there a defensive wall erected in front of him, but there was also the constant danger of a turnover leading to a dangerous counter attack. Anyone looking for examples can find them in Magath’s final game (30/1/2007, 0-0 against VfL Bochum).

This mostly diagonal dribbling against the mass ranks of the opponents out from his full-back position was a trademark of the first third of Lahm’s career, one which he would later completely drop. This happened, above all, because on the one hand, due to crucial transfers like Ribéry and Robben, he was no longer the only player who could break the lines and beat players in one-on-one situations. On the other hand, it was also because as the tactical structure changed, Bayern developed fundamentally different attacking ploys which made such risky actions unnecessary.

Self-discovery years 2007-2009

It is telling that Lahm, when he first expressed his desire to move to the right side in 2007, was the only one talking about defensive motivations. In the media it was only mooted that he would probably be able to cross better from the right side with his strong foot, though he would also forfeit his chances at scoring [sic!], as he would no longer be able to do what Robben would later do and cut inside to shoot with his stronger foot. Quite apart from the fact that in this context far too many who gave their opinions were clearly finding it hard to forget Lahm’s goal in the opening game of the 2006 World Cup against Costa Rica, there showed a discrepancy between the media focus on his offensive qualities and Lahm’s actual understanding of his role, namely to predominantly be a defender.

At the time, in interviews Philipp Lahm was starting to speak of considerations that went beyond the usual “I-play-where-the-boss-puts-me”, documenting a process of maturation. If Lahm was still pleased in his early years under Magath to have made the breakthrough, and was primarily focused on establishing himself (at Stuttgart, in the national team, at Bayern), in the second Hitzfeld era he would begin to increasingly differentiate between his role at the club and on the pitch, developing his own ideas. The trigger for that may have been Bayern’s crisis during the 2006/07 season, when it became conceivable for the first time that the way the club was developing and the way that Lahm was personally developing were not exactly in harmony. The fact that he extended his contract in spite of that in 2008 seems, in hindsight, to sell quite well as an emotional decision. Philipp Lahm comes from Munich and grew up with the Rekordmeister, and so in that sense the thought of leaving his home would not have been an easy one for him to process. However, it has never been his style to pledge his allegiance – he has always been too rational in his planning to want to rule out any future possibilities in such a way.

Here as a perfect example we ought to mention his reaction to the immense praise he received, most of all following the opening game of the 2006 World Cup. Lahm had returned to Bayern for the 2005/06 season, but, due to a ruptured cruciate ligament sustained while still at Stuttgart, was out until November. In the second half of the season, he had to share the left-back role with Lizarazu. He still hadn’t been a professional at Bayern for a full year, still hadn’t gone into a season with his home club as a key player. Yet he responded to questions from journalists about possibly being in the sights of clubs like Barcelona and Real Madrid not with comments that a Bayern fan at the time would have liked to hear. That he was already at a top club, or that he was just looking forward to going into a complete season with his club at full fitness. On the contrary, he laid his cards on the table and made no pains to nip the coming transfer rumours in the bud, but rather wanted to “get to the end of the World Cup, and then we’ll see.”

(Photo: Photo by Bongarts / Getty Images)

Whatever it was that eventually tipped the balance in favour of him renewing his contract, whether it was his love for the club, the financial offer or the prospect of the captain’s armband. Philipp Lahm must have listened to Uli Hoeneß and Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, how the two of them planned the future of the club, and that vision must have convinced him, or at the very least seemed passable. In an interview with SPIEGEL in May 2008, he names one aspect that for me personally seems particularly plausible, because he sticks to the blend of connection to his home and ambition that is so typical of Philipp Lahm: “But I asked myself, what I would do if something big happens here at Bayern and I’m not there.”

Ultimately Philipp Lahm would probably have preferred to stay put at FT Gern his whole life. It took a long time for him to get his head around being simply too good for that club. The only similar thing that happened for him at FC Bayern was in the period around 2008: on one hand we have FC Bayern, not making it past the quarter-finals of the Champions League time and again, and on the other we have the footballer Lahm, who has attracted the interest of numerous top clubs, and similarly to Michael Ballack before him he could have solved problems of that nature overnight by simply clicking his fingers and moving to one such top club.

In any case, it was clear for all to see that Lahm was already of international quality, and in that perspective actually stood in a better light than the club Bayern Munich itself. And not enough can be said for how, in the chaos of the Klinsmann era, in particular after the 4-0 beating against Barcelona in 2009, he didn’t seek the exit door, but rather carried on believing that the situation could be overcome and that he could win the Champions League with Bayern. He linked his destiny, his career, and his personal chances of success with those of the club, and “sacrificed” his best years for a project that – as he himself said – wasn’t doable overnight, but would be realised over several years. In this context it’s easily explained that in November 2009 in an interview with the Süddeutsche Zeitung he sounded the alarm at the club’s lack of development. He saw the development, and thus the eventual prospects of success of the project, as seriously endangered.

He had made sacrifices for the project, and here his contract extension is not what is referred to: he had changed his game, put his personal interests to the back of his mind, and so became the incarnation of serving the team. In 2007/08, with the signing of Marcell Jansen, Lahm was able to switch to the right-hand side, where according to his own evaluation he’d be better able to defend, because among other things he could go into tackles with his stronger foot close to the opponent, and also pass the ball down the line under pressure with more precision. He was fully aware that he would restrict his own personal glory, including in his public perception, but for him it was more important to fulfil his role as a defender as well as possible.

Lahm had recognised that he would help FC Bayern at the highest level if he – now that in Ribery they finally had another world class creative player – were to provide the team with more defensive stability, rather than bombing up and down the line and going into risky one-on-one situations that could expose the defence. He rationalised his game and focused on his core tasks as a defender: a little more Maldini, a little less Dani Alves.

He had to force this change to his game against genuine resistance. It wasn’t entirely appreciated publicly: Kicker magazine, in their German football ranking lists, banished him to the “Ones to watch” section for the first time in his career, and at the 2008 Euros the pressure in the media rose to such a level that Joachim Löw summoned him back to the left side of defence during the tournament. Above all that was linked to Marcell Jansen’s poor form, and he was also the reason why Lahm appeared as a left-back under Jürgen Klinsmann at club level too, in the 2008/09 season. In a very hush-hush operation, Jansen was sold to Hamburg, and Bayern signed Massimo Oddo on loan, who would go on to share Lahm’s preferred position with Christian Lell.

For Lahm it would have been easy to put his personal interests front and centre and to insist on his position, as Martin Demichelis did in March 2008 before the Cottbus game when he refused to play in midfield. Lahm actually helped out in that same position previously in November 2007 in Germany’s 2-1 win over England at Wembley, and put in such a good performance that he would have been a logical alternative in that position too.

But he complied as he always did, and played in the position where he was most required. The problem that he wasn’t consistently played in the position he was best (or at least felt most comfortable) would go on to be a theme throughout his career, at both international and club level.

What’s typical about that is that Lahm has always had to compensate for his team-mates inadequacies on the pitch too: be that directly, because he had to deal with catastrophic passes under a lot of pressure, so often making it seem like the easiest thing in the world; or indirectly, by always attempting to maintain balance in games, like a thermostat regulating the ‘temperature’ on the pitch. If the team played too wildly and direct, Lahm would set about calming the game down and exerting control. If the game was too static, Lahm initiated faster moves, getting the ball to circulate more quickly, and would make runs to support his team-mates on the flanks over and over again, to offer a pass option or at least to distract the defence’s attention from the player on the ball.

He undertook these painstaking runs, knowing in all likelihood he probably wouldn’t even get the ball since Robben or Ribéry would rather shoot or dribble, countless times. He didn’t once complain afterwards, or react with a derogatory gesture, but rather got straight back into position after a turnover without grumbling. And it’s probably an open secret that a lion’s share of the praise lavished on attacking players like Ribéry or Robben has Philipp Lahm and his permanent support and prudent back-up to thank.

At the end of the 2008/09 season, Philipp Lahm was just 25 years old, had already appeared in the Team of the Tournament at the 2006 World Cup as well as the 2008 Euros, had been the definition of world class for six years in both full-back positions, shone at Wembley, even while playing in a third position, and had shown the first glimpses of strategical thinking. At that time he was Germany’s best outfielder, he had sorted out some initial flaws in his defending, and regularly compensated for the shortcomings his team-mates’ on the pitch as well as those of his coaches on the touchline. And in spite of that, the best was yet to come.