“Carlo needs to work smart, not hard” – Martí Perarnau on Bayern and his new book

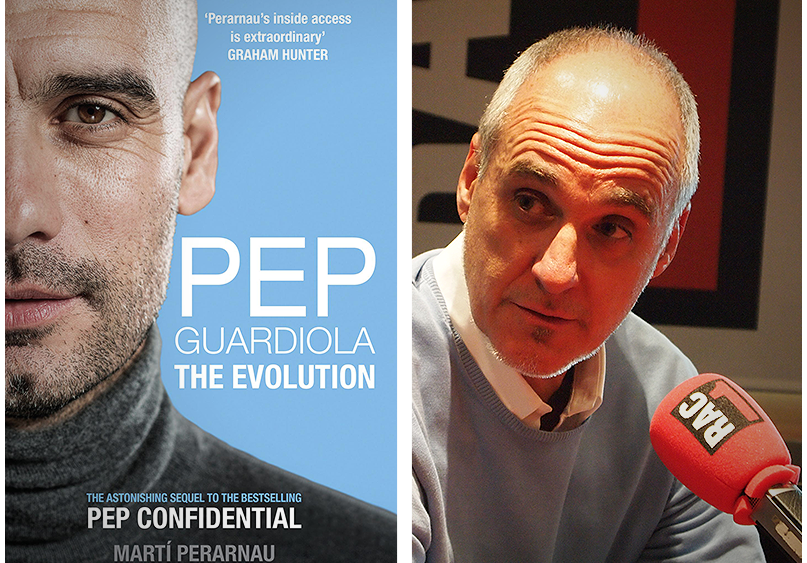

Martí Perarnau, you’ve been working with Pep and Bayern for three years now. Is this chapter now closed for you or is there something else on your mind?

I’m currently working on a new book about the tactical evolution in football since 1860. It’s a crazy, non-commercial project. Usually we think that football as we know it started evolving about 40 or 50 years ago, but it truly didn’t. In the book, for example, I write about Edward Niedham, the captain of Sheffield United, who wrote about build-up via the central midfielders – in 1901. Imagine that: 115 years ago, players were thinking about tactical development.

Is Pep interested in those historical topics?

Very much. He doesn’t know too much, he’s not an expert on the history, but he is definitely interested. For instance, if you look at Messi’s positioning as a false nine in Barcelona: The idea came up in a talk Guardiola had with Juanma Lillo, one of the greatest experts on the history of tactics, who was telling him about players like Adolfo Pedernera who had played in this position before.

When did Pep add this experience to the Bayern game?

Take a look at the game against Cologne in October 2015. He played a 2-3-5, the pyramid system. People on Twitter were making graphics to compare it to the system of Hungary in the 1950s. He read that and told me: ‘Look, they’re saying that my team has played like one of the greatest national teams in the history of football’.

Like a tree at Säbener Straße

Did your writing process change between the first and the second book?

The first book was something I had planned well in advance, I tried to describe Pep’s life in Munich during his first year. It was a very chronical thing: What happens during training sessions, team talks, matches, afterwards in the players’ lounge. After that, I originally didn’t have a second book planned, but well, here we are now.

How did your relationship with the players develop in the years after your first book?

During my first year, the players and I were all quite shy. Some friends called me a ‘tree at Säbener Straße’ (laughs). After everybody had read my first book, they knew that they could be more trustful with me.

Did you have a special relation to one player in particular?

I have been talking a lot to Xabi Alonso, who has been very open to me. Manuel Neuer, Philipp Lahm, and David Alaba as well. Philipp, Xabi, and Manu are very serious players – so I often enjoyed talking to David, who is just a very funny guy.

What did a typical day at the Säbener Straße look like for you?

If training started at 11 in the morning, I would be there when the players arrived and talk to all the people around. I had lots of fun with the security guards, most of them only talking Bavarian (laughs), but also tried to get an impression from the gardener, the women’s team and of course most of the time with Pep’s staff. Then I would watch the training and speak to some players or Pep after that, about the plan for the weekend or general things. After that, I’d go to my room at the Wettersteinhotel and write everything down.

Did you ever travel with the team?

No, I tried to be as unobtrusive as possible. I was granted full access by Pep but didn’t want to disturb the team. In some moments you need to step aside, because as soon as you start to have problems with the players, the book project is ruined. That’s also why I tried to be quiet on Twitter and not attract too much attention.

Did you become a fan of Bayern Munich while writing the books?

I mostly tried to keep my emotions out of the writing process and remember that I’m a tree at the Säbener Straße (laughs). People often criticised me for being a friend of Pep and writing about him from a special position. I’d correct that: I’m not a friend of him, I got to know him in 2013 and we have a trustful relation – but it’s still extremely professional.

In your book, you didn’t only talk to people inside the football business, but also with creative artists like the chef Ferran Adriá or the conductor Christian Thielemann.

For me, Ferran Adriá was very important. I met him in 2015, in the middle of the project. By then, I knew Pep very well, had talked to him a lot – but when I spoke with Ferran Adriá, I got to know him even better than when I was watching the practice at Säbener Straße. Ferran has an open, different mind and already knew Pep from his time in Barcelona.

So they knew each other quite well?

It’s not about Ferran knowing Pep, it’s more about them having the same way of thinking, the same ideas of life, which he shared with me.

Is the positional play vanishing already?

Now Pep Guardiola is at City, where you were saying he wants to “create history”. Is this a similar approach to when he arrived in Munich in 2013?

It’s actually very different. When he came to Munich, Pep was a young man who had only lived at home so far. There was La Masia, Xavi, Iniesta, Messi, the Cruyff football – he was in his comfort zone. In Munich there were so many new things: the culture, the language, the legends here and their heritage. In Manchester it’s the opposite: You won’t find the history of Bayern or the playing style of Barcelona.

Would you say that Pep’s work in Munich will have a long-term effect or has Ancelotti already changed too many things to still see Guardiola’s handwriting?

Bayern have made a very impressive decision with Carlo Ancelotti. He is the best coach in the world when it comes to managing the feelings of a team. While Pep has the profile of an architect, Carlo is working more like an administrator. It’s a good step, but Carlo will need more time to adjust the tactics of the last three years. Carlo can perfectly administrate Pep’s tactical legacy and continue to send a competitive team out on the field. The spirit of winning every single match is the true heritage of Pep at Bayern – and Carlo can keep this at the level of the last few years.

From a fan’s perspective, it might be hard to watch the miraculous “juego de posicion” vanish.

I wouldn’t say it’s vanishing, it might just not be as clear as last season. You have to keep in mind that the positional play is extremely hard to practice. The players have to work for it each day and stick to the strict principles of the game. If they don’t, there will be major problems. It’s small things that change everything.

Give us an example.

For instance, if Arturo Vidal adjusts his position only a little, Xabi Alonso will play better. When Xabi loses too many balls, it’s always about his colleagues being too far away. It’s similar to Busquets at Barcelona. Take Barcelona’s recent game against City: Andre Gomes and Ivan Rakitic were too far away from Busquets and as soon as Silva pressed him, Manchester got a chance.

Let’s stick to Xabi Alonso. He doesn’t seem to be well-protected at the moment.

That’s the problem. The positional play has many strengths, but it does also have its weaknesses. One of the main risks is the position number six. The first theory to protect this position is to place another player right next to him, a second number six. But in this case you would destroy the positional play, as one of its main principles is to be escalated in the midfield.

Jupp Heynckes won the Champions League with this system.

And Pep used it too. He played Alonso and Vidal, Lahm and Kroos, or Schweinsteiger and Alonso – but only in very special moments. He mainly trusted in the alternative protection of the number six, which is either putting it far back between the central defenders or to play the wing-backs close to him. But that is not it: You’ll always put too much pressure on the number six if the eight and ten are too far away from him. As soon as Thiago and Vidal can make Xabi’s line of passing easier, this problem will disappear.

After reading your book, it felt like Xabi Alonso played an important part in Pep’s football at Bayern. On the other hand, it was hard for him to let Toni Kroos leave to Real Madrid. Would Kroos have been the better Xabi Alonso, who was just the best replacement for him?

To answer this question you have to add that Toni Kroos is a different player from Xabi Alonso. Xabi is the perfect number six for the positional play, but not in any other model. Kroos is more versatile then Alonso, in my opinion he is much better as a number eight. In Pep’s first year, Toni Kroos played as number six in the Supercup against Chelsea, mostly because Bastian and Javi were injured. After thirty minutes, it became clear for Pep and Dominic Torrent that he was struggling against Torres, so they put Lahm in the position for the first time. He could demonstrate his strengths much better after that.

So the ideal situation would have been to keep Kroos and still buy Alonso?

Xabi as number six, Toni as number eight and Thiago as number ten – that would be the most amazing midfield I could think of. Maybe add Philipp Lahm as false right-back and it’s perfect.

On the second page, Martì tells us more about a magical night in Rome, a loss in Wolfsburg and Philipp Lahm influencing Pep Guardiola.

Practice under Pep is a “master’s studies in a short time”, says Xabi Alonso in your book. How long did it take the players to adapt to his exercises?

I’d say about three months. In September 2013, the team didn’t play very well, but if you remember the show at the Etihad Stadium in October, you could see that by then the players understood what Pep’s idea was about.

Pep was extremely demanding in his practice sessions. It must have felt quite good for the players to let go a little bit?

It’s the big challenge for Carlo now. You can’t make the players forget what happened in the last three years, so they will of course try to stick to their positional play in some ways. But they won’t be able to do that without the right exercises.

But is it such a big deal to lose a few percentages in comparison to last year? Won’t that still be enough?

Let’s take a look at an easy example: Usually passing the ball is a problem of a tenth of a second. When you play at the Vicente Calderon on dry grass, the ball won’t run very well, while under rainy circumstances at the Allianz Arena it’s quicker. The latter is way more difficult to defend, because the ball is just this little bit faster. Pep applied this logic to his exercises, he used the rondos to make the players gain this decisive tenth of a second. If Carlo Ancelotti decides not to use rondos for winning the extra-tenth, he will have to find other ways.

Which ways for example?

Taking the rondos away might have seemed like a big decision. But, if you take a closer look at the way Bayern is training under Ancelotti, you will see that it is not far away from Pep’s ideas. The difference to Pep is that Carlo needs to work very smart, not very hard.

Another interesting comment you make in your book is that Pep couldn’t implement his thoughts in the youth teams. Why was that?

When he arrived in 2013, he didn’t know about a lot of inside work at Bayern, one of which was the youth strategy. He talked to Matthias Sammer, Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, and Uli Hoeneß and they told him that wasn’t necessary to have the youth teams play the same way as the first team. For Pep, that was no problem at all. It was different from Barcelona of course, but it’s a club decision and he has to accept it. Just like in the matter of the Kroos transfer, he disagreed but accepted it. For me personally it was a mistake of him to not insist on Kroos staying or the youth coaches working together with him.

He was able to adapt to many things at Bayern and to Germany in general. Why was he struggling with the media?

It’s his personality. For a person from Catalunya, it would be a demonstration of the desire to be one of us if a German coach came to Barcelona and started talking in the domestic language. That was his approach in Munich, though it’s not appreciated in the same way here. In my opinion, it was a mistake; if you listen to him explaining things in Spanish or even English it’s way more easily understandable than in German.

Praising every opponent was another issue for the local media. Everybody thought he was exaggerating.

He really always meant it. I remember the morning of the day before the match at Benfica. I had just gotten into his office and he immediately told me that it would be one of the craziest teams he had ever seen, it was a perfect Sacchi-esque organisation in the defense and so on. He kept talking enthusiastically for another 20 minutes – though it was a private conversation. When he said the same things in the press conference a little later, everybody thought it was tactics to praise the opponent.

His analysis of the rivals seems to be the craziest part of Pep’s work as a coach.

He analyses the rivals in a way nobody else does. Everytime he finds some skill in the rival, he starts fearing it and that is why he always praised them in the press conferences.

Let’s walk through the three years of Pep at Bayern and pick some games as an example. What comes to your mind when I ask you about Pierre-Emile Højbjerg?

You want to talk about the Pokalfinale 2014, right? (laughs)

Yes, please.

It was an extremely emotional match. Bayern had lost against Madrid, many players were injured and Dortmund was the ultimate opponent in Germany. With David Alaba injured, Højbjerg was the only option as a right back. He played a fantastic match, but it was also the moment of a broken relationship.

How come?

After playing in the DFB-Pokalfinale, Højbjerg thought that he was in a position to always play. Pep told him to wait a little more, but he didn’t listen and in the end left the club.

Pep’s influence on the mental strength

A few months later Bayern beat Roma 7:1 with a stunning performance. Was this the ultimate Guardiola game?

It’s a great example for how Pep wins matches by analysing the rivals. He knew that after ten minutes Totti would stop marking Xabi Alonso, who then had the space he needed. He decided to play via the left side and created a vast space on the right. Alaba, Götze, Müller, Lewandowski – they all played far left and opened up the room for Lahm and Robben, who then led the team to victory. Usually the matches were won by the players, but in this case it was Pep who deserved the credit.

Bayern also suffered some surprising defeats. What happened in Wolfsburg in early 2015?

That was a mistake by Pep. In the winter break, he tried to implement a more direct way of playing. Normally, when Bayern managed to win the ball in counter-attacks, they would try to play directly to the goal. But if that was not possible, they would calm the game down and start a new attack with the positional play. However, back in Qatar 2015, he told the players to always play the direct pass, no matter what happened. The team didn’t play well, lost by a large margin, and Pep decided to go back to the basics again.

In the very last months of Pep’s era, it felt like the team wasn’t only winning because they were playing better, but also because they showed great mentality, like in the second leg against Juventus. What was Pep’s influence on the team’s mental strength?

The key at that time was that the players and Pep were as close as they could be. In spring 2015, when there were only 14 players available due to injuries, they created a special bond between each other. From then on, all the tactical development was not as important as the winning spirit inside the team.

Did we get to know “pragmatic Pep” in the third year here in Munich?

It might seem so. Before I got to know Pep myself, I had an image of him as a romantic artist. But that is not true. He likes to win, that’s all. If possible, he will use his style for it – but if not, then he will change it to win. But it’s true: He adapted to the German style of football especially in the last year.

Seeing him cry after the last game was one of the most emotional moments in the younger history of the club. How did you watch this emotional explosion?

What amazed me at the Olympiastadion that night was the insanely high tactical level of the match. It was not an emotional match, but after the game Pep went to celebrate with the fans for the first time.

Why didn’t he do that earlier?

It was his way of thinking. A Bayern win was the achievement of the players, not the coach. He felt like it was their stage. But it was Philipp Lahm who changed that.

What did he tell him?

He was the first to tell Pep that it’s not the team and the coach, it’s what they achieve together. Lahm showed him that it’s a mistake to think Pep’s way, who had the idea of the players working on the weekend and the coach working during the week. Instead it’s that everybody works together at all times. And if Bayern wins together, players and coach celebrate together. In his last night with Bayern, Pep learned his most important lesson from Philipp Lahm.

Great interview it’s always interesting talk about pep

If i had a time machine! I want this pep back!

So that we could have another humiliation against Spanish team. This time it will be Sevilla ‘s turn

Impressive interview and quite the achievement for this wonderful blog. Keep up the good work!

[…] Barca, for example, was developed during a conversation between the pair, according to the author Marti Perarnau, whose two books on Guardiola have garnered great […]