Tactical Review: FC Bayern München – Bayer Leverkusen

Ivo Karlović is one of the most intimidating opponents in world tennis. Not only does his 6’11” frame dominate the skyline on the court, but his height gives him a unique, increased serving angle down into the opposite service box. Having a bigger target to aim for combined with his excellent technique and power in the serve, the Croatian is famous for racking up incredible ace counts in every game he plays. The advantage he gains from his serve serves as a thorough examination of his opponent’s technique and, more importantly, resolve that they will unlikely receive against any other player on the tour.

Yet, despite his supernatural service, Karlović has struggled to get the results of his fellow professionals. He has an unspectacular grand slam best of a single quarter final appearance in 2009 at Wimbledon and an overall win rate of just over 53%. This points to technical deficiencies in his all-round ability. His ground game is weak and his backhand in particular is uninspiring. Behind the serve is a soft underbelly that can be exposed.

Perhaps it is this weakness that makes him one of the more interesting and endearing players on the ATP tour. So reliant is he on his serve to win points that he tries desperately to keep the length of each point short by playing aggressively to the net – a style that is rare in the modern game, dominated by baseline slogging. Karlović needs to keep his opponent on the back foot at all times if he has any chance of making up for his deficiencies elsewhere.

It is in this way that Ivo Karlović’s game resembles Bayer Leverkusen’s struggle against Bayern Munich on Saturday. Leverkusen under Roger Schmidt play with one of the most formidable and extreme pressing systems in world football, making it very difficult for teams to play their own game and often forcing mistakes from them in key areas. However, Munich were able – through some typically Guardiolan organisation – to repeatedly break free of this pressure and launch attacks on the exposed Leverkusen defensive unit – a key factor in the reigning champions’ victory.

Bayern’s Solution to the Defensive Problem

The home side came into the match off the back of a costly victory away to Hoffenheim. With both their central defenders from that day, Benatia and Boateng, unavailable through injury and suspension respectively and potential replacements Badstuber and Martinez likewise unavailable, Bayern welcomed Leverkusen with only one central defender, Dante, in their squad. One of the most important tactical questions of the match would prove to be who Guardiola sent out in defence.

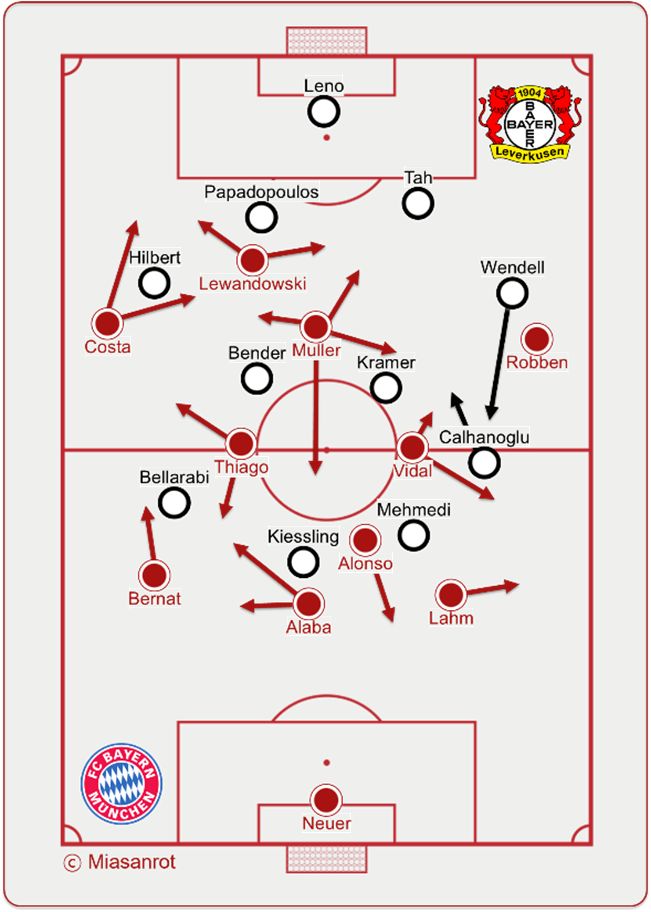

Bayern lined up in what is best described as a 3-3-1-3, with Alaba playing as the main central defender, flanked by Bernat and Lahm. Thiago made his first start of the season on the left of the midfield diamond instead of Vidal, perhaps due to the Chilean’s poor positioning in the build-up phase leading to a lack of connectivity with Costa. In Bayern’s first game against Hamburg especially, Vidal’s inability to properly support Costa in the wide areas were a major factor in the dull and lifeless first half.

In addition to the benefits gained with his movement, Thiago’s press resistance also makes him a great player to play in a fixture this uncomfortable. His ability to move the ball away from the pressure zone with minimal touches and therefore in much less time is hugely beneficial against a team that plays with as strong a ball-orientation as Leverkusen do.

Just as Thiago is press resistant, Xabi Alonso is most certainly not. His inefficient positioning makes him, and by extension the teammates he is connected to, very vulnerable to pressure. Given that Munich were coming up against the most aggressive pressing team in the Bundesliga in Leverkusen, Guardiola had to find a way of allowing Alonso to play his cruise-missile-esque passes around the Leverkusen block without risking him being pressed from behind by the likes of Kießling and Mehmedi. The solution was to have him drop deeper, between Lahm and Alaba, essentially giving Bayern a back four in possession. Interestingly, this is the reverse of the traditional salida lavolpiana that Guardiola popularised at Barcelona. While the holding midfielder usually drops in between the two widened central defenders as the full backs push up to create a back three and an extra man in midfield, against Leverkusen, Alonso dropped in to create a back four with the loss of a man in midfield. This indicated a clear wish to avoid playing inside the B04 forward press.

Leverkusen’s Press

At the heart of the Bayer Leverkusen press under Roger Schmidt is an unexpected and delicate equilibrium. Lying way out on football’s third Lagrange point, in its purest form it dispels conventional wisdom regarding pitch coverage and stability. The fundamental idea behind Schmidt’s press is to create situational local compactness around the ball in the pressing zones – whatever they are chosen to be – in order to hurry the ball carrier into a poorly executed action. This can either be intercepted by pressing players with access to the passing lanes or, should the initial pass or dribble be successful, by players in the second wave of pressure picking up loose touches. Such an emphasis on local compactness around the ball, or ball orientation, leaves the weak side of the pitch completely free, with the idea being that the press will prevent the transfer from occurring.

In this symbiotic relationship between the means and end, the slightest mistake can upset the equilibrium of the press and render it useless. For example, if the press leaves even one passing lane away from the pressing zone open, the ball can be easily transferred out to the weak side, leaving the entire team to make recovery runs to the opposite side. Therefore just as it is a requirement for Leverkusen to maintain strong ball orientation to execute their press, it is equally important for them to press effectively in order to prevent the weak side from being exposed in the transition.

However, whilst their horizontal compactness is strong, B04’s central midfield pairing of Bender and Kramer have a propensity to push high up whilst pressing, resulting in poor vertical compactness between the midfield and defensive lines. Should the press be bypassed, there is a lot of space behind the midfield for the opposition to attack. Given that Bayern’s positional play places an emphasis on the importance of the free player between the lines, despite Leverkusen positioning and pressing centrally to prevent the vertical pass, they often found themselves attacking in numbers directly against the Bayer defence.

Bayern’s Solving of Leverkusen’s Approach

Just as an opponent of Ivo Karlović knows that if he can deal with the barrage of services raining down at him from across the court, keeping the points long, then he can do some damage to the weaker parts of Ivo’s game, Leverkusen’s opponents know that if they can play out from the press then they will find joy in the swathes of space left open. The problem for teams facing B04 is that they usually lack the connectivity, positioning and movement to play themselves out from the pressing zone – not a problem that Bayern face, however.

Leverkusen’s pressing influenced how Bayern functioned in their half of the pitch. As previously mentioned, Xabi Alonso dropped in to form a back four in possession in order to take him out of the pressing zone. This gave Bayern a long-passing threat from the back which they could use to bypass the pressing zone completely.

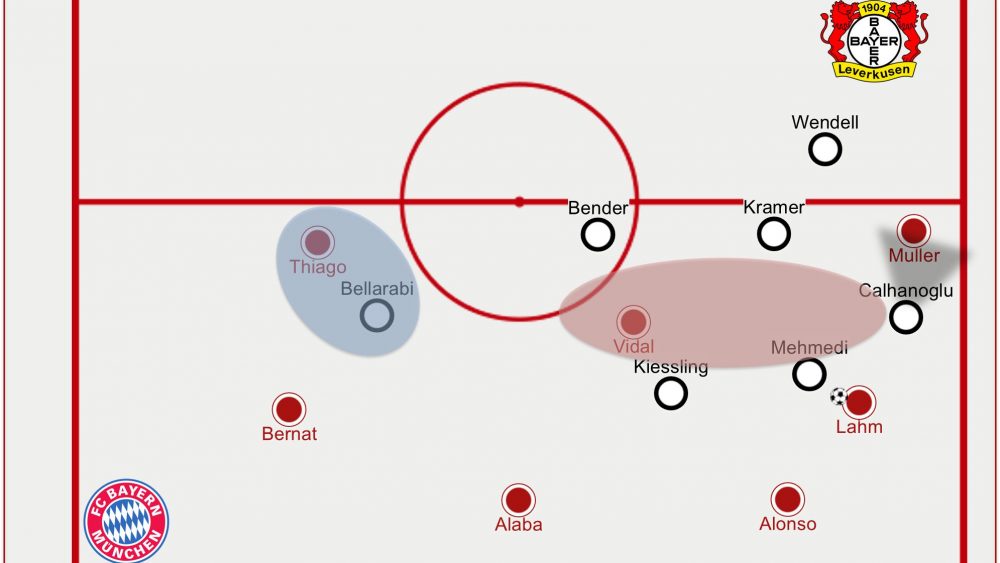

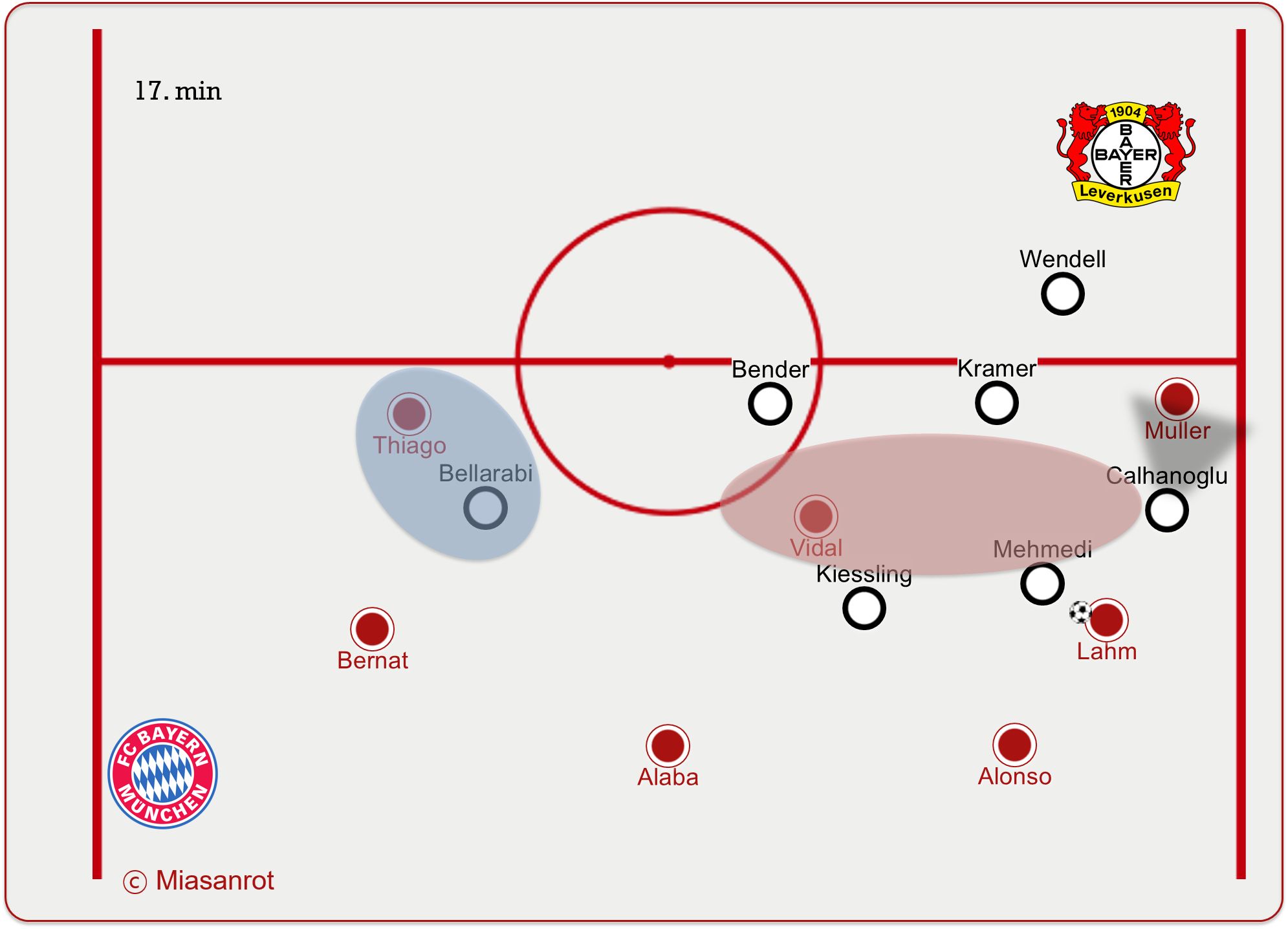

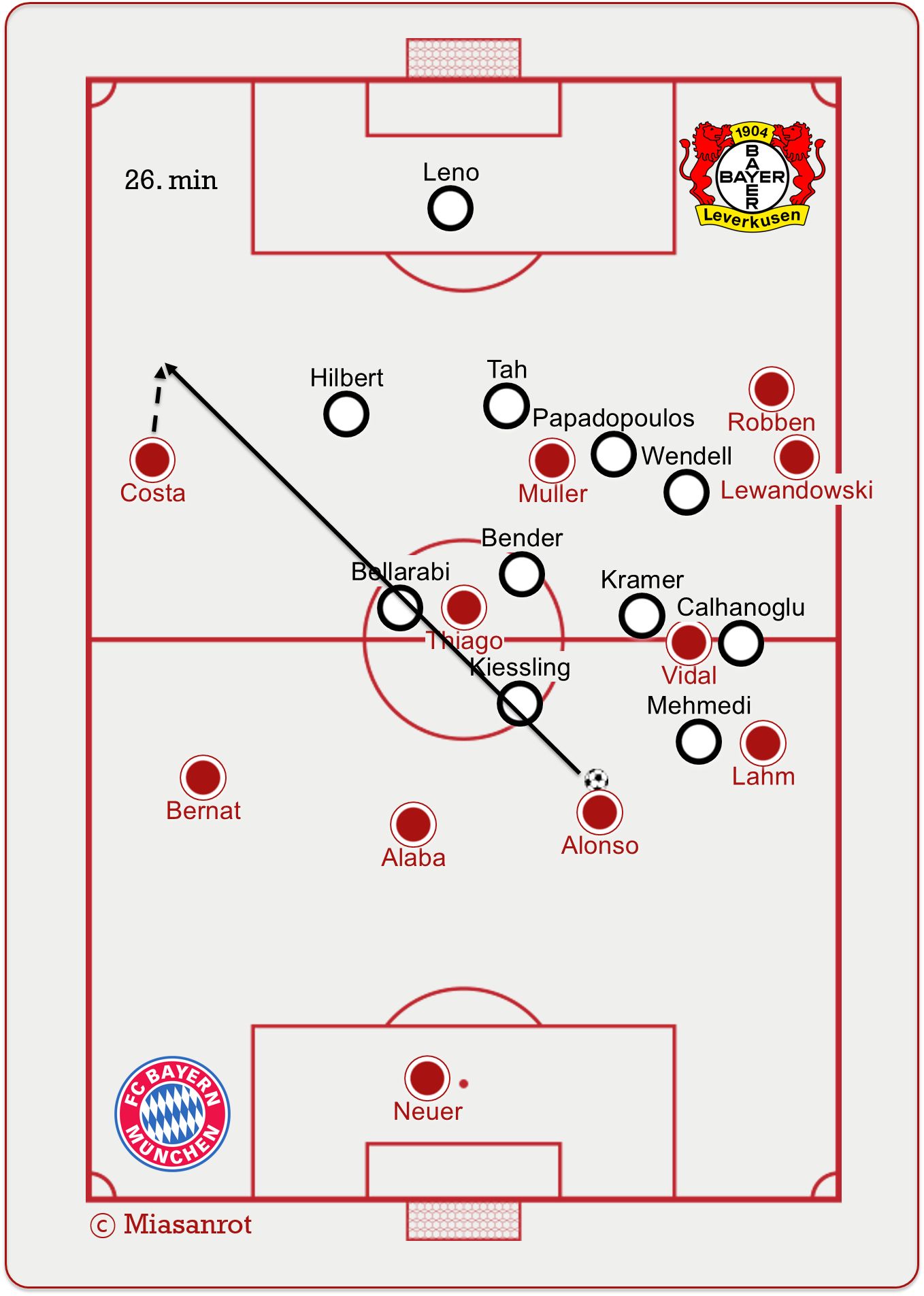

Leverkusen press in a 4-2-4 shape, with both central midfielders heavily involved in screening the space behind them. With the exception of Bellarabi, who is drawn away by the movement of Thiago, Leverkusen’s ball-orientation is evident here, with their entire pressing unit positioned on the right side of the pitch.

The pressing zone here is highlighted in red – this is the area which Xabi Alonso would usually operate in if he weren’t to be subjected by aggressive pressing. Whenever Bayern gain possession in this area surrounded by Leverkusen’s pressing players, they are immediately surrounded by everyone who has access – stifling the play and risking turnovers in dangerous areas.

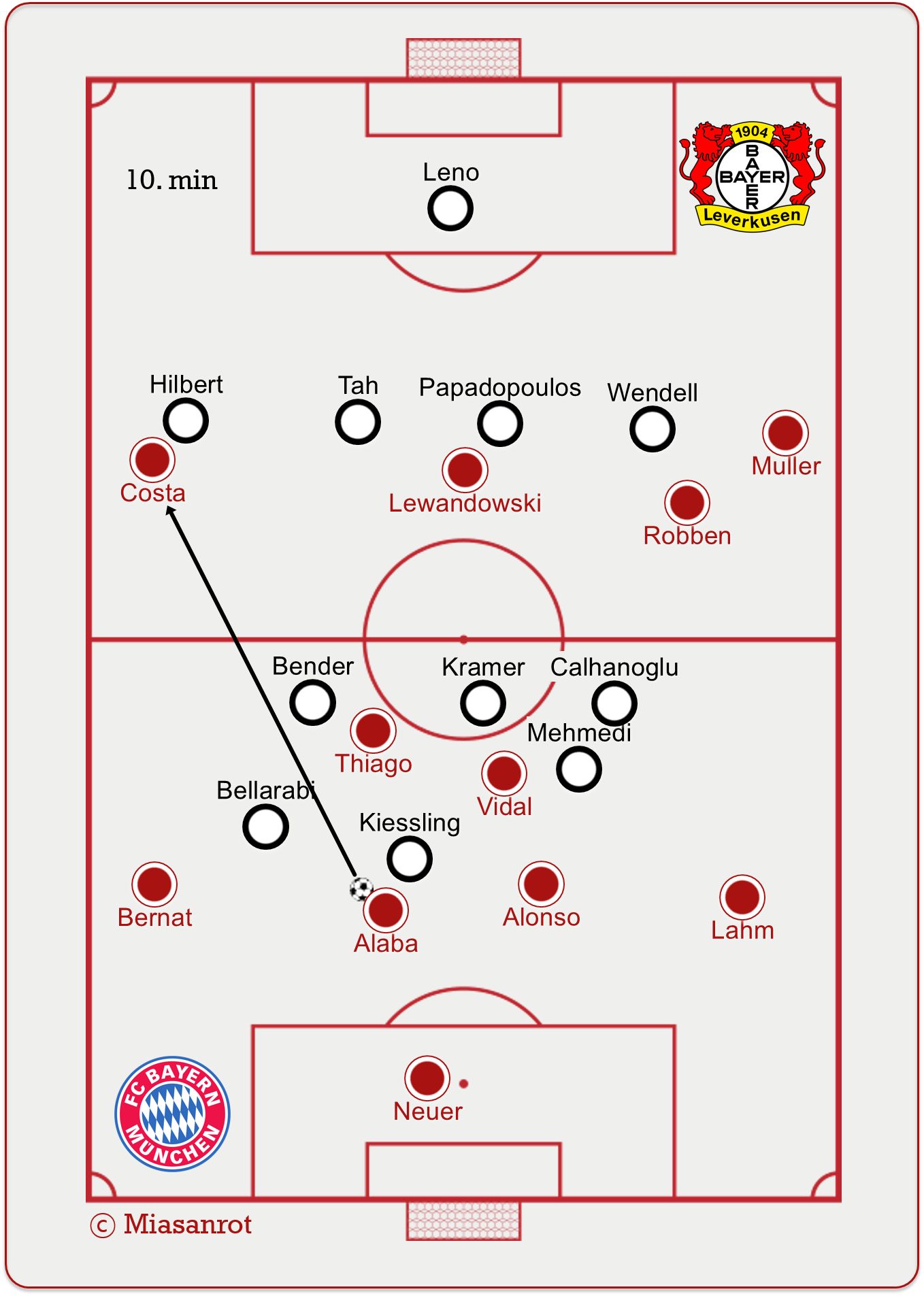

In addition to the presence of Xabi Alonso in the back line, David Alaba also assisted in dismantling the press. His vertical passes, especially out to Douglas Costa on the wing, were devastating and often played Leverkusen’s front six players completely out the game.

Alaba’s quarterback-like passing cuts straight through the Leverkusen press to Douglas Costa who can attack the full back 1v1. Leverkusen’s back line, wary of the pace of Bayern’s front line, hold a line hugely disconnected from the midfield. With Bender and Kramer anchoring the back of the press, there is a huge space in between the lines for Bayern to drop into to receive the ball. In this particular situation, Hilbert makes a good tackle to force the ball out of play and slow the game down again, but this happened time and time again.

Once more, Bayern exploit Leverkusen’s horizontal compactness in their ball-orientation. Alonso, from the safety of his central defensive position, is able to get his head up and switch diagonally out to the underloaded weak side. From the resulting 1v1, Costa crosses for a Muller goal.

With these situations arising time and time again, Bayern eventually wore Leverkusen out. Struggling to control the press and being constantly bypassed, the visiting team often had to make large recovery runs to get back into position.

Fitness-guru Oliver Bartlett has helped build one of the fittest teams in world football, but their inability to restrain Bayern’s build up left them chasing shadows at times – the front players in particular looked drained by the end of the game.

Summary

Looking back, it could be said that Bayern’s lack of traditional central defenders helped them overcome the fearsome Leverkusen pressure. Whilst Boateng would have done a similar job to Alonso in playing booming diagonals over the pressure zone, Benatia would almost certainly have been targeted and Alonso would have had to either play in midfield, susceptible to pressure, or drop into the back line – taking yet another player out the midfield line, causing a disconnect. Leverkusen will come up against few teams this year who will control a game as well as Bayern did – Tuchel’s Dortmund looks like the next real examination of their style – and they will no doubt continue to dominate games against the rest of the league playing the way they did. As long as Roger Schmidt can continue to have his players embody the serve of Ivo Karlović rather than his backhand they will anyway.

September 5, 2015

September 5, 2015

This goes to show that Pep takes every detail into consideration. He knows if his team exploits the weakness of Bayer, it will lead to a 1V1 situation which led to a goal. To me, Bayern do not need regular CBs…just players!